In the depths of the pandemic, Greek photographer Eirini Androulaki joined a collective artistic endeavor to respond to 200 suicide notes written between 1821 and 2021. In a time of uncertainty, mass global panic and resurfacing stigma around illness, care and responsibility, one letter caught her eye. It was written more than a century ago by a teacher named Stylianos Balmetakis who, when struck by tuberculosis, had chosen to take his life rather than put the lives of those he loved at risk.

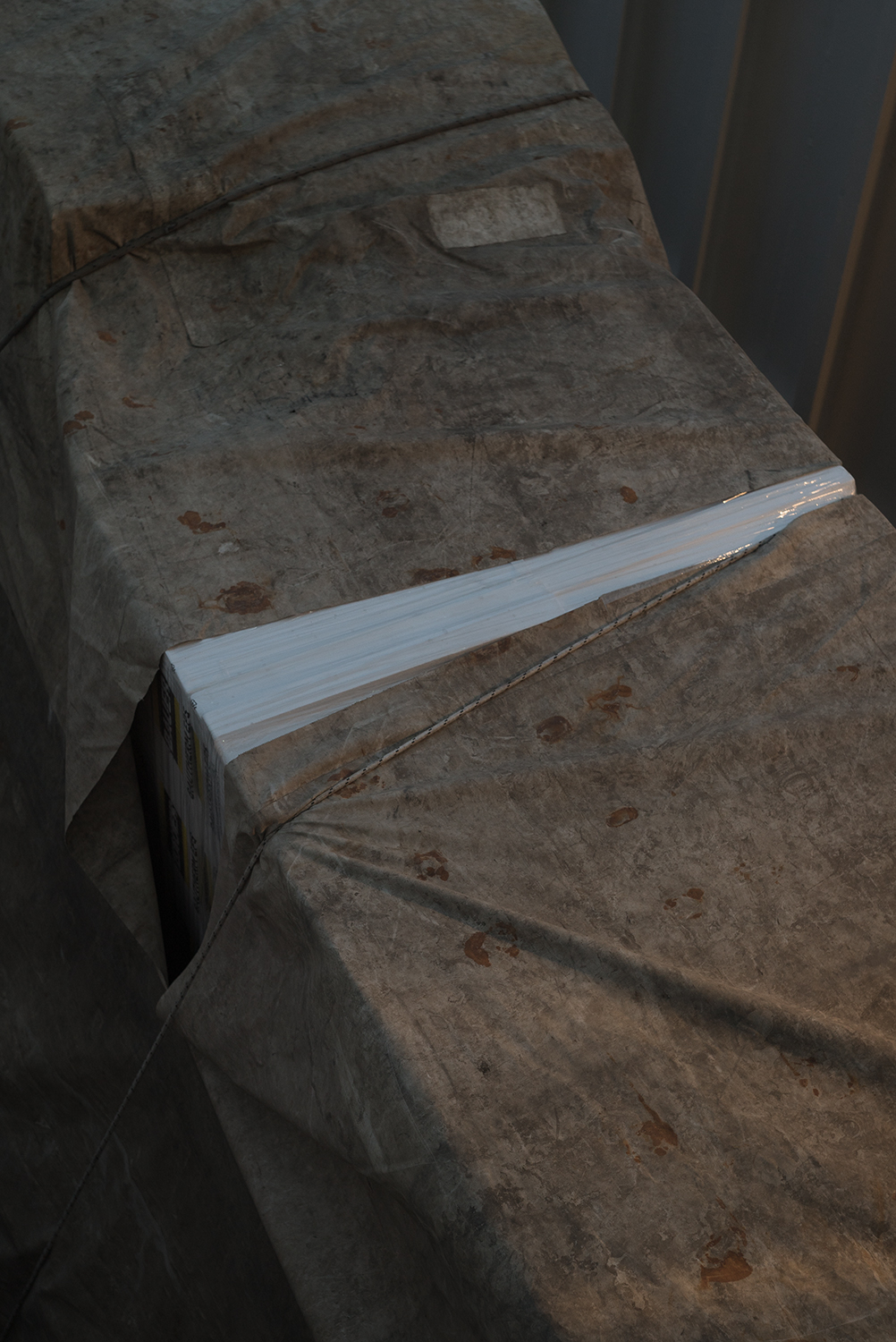

In her ongoing project Didn’t Mean to Keep You Waiting, Androulaki inhabits the gaps of Balmetakis’ story in part-tribute, part-investigation into the difficult questions that this complex side of human experience tends to provoke. Working with archival material and her own elliptical photographs made on Folegandros, she finds a metaphorical language to tell a story that can never be fully complete.

In this interview with LensCulture, Androulaki speaks to Sophie Wright about bridging time through photography, the ethical dimensions of working with incomplete subject material and the enigmatic title of the work.

Sophie Wright: You’ve studied political science and cinema, both traces of which I’d say could be found in this project. Can you tell me a bit about how you arrived at photography?

Eirini Androulaki: Alongside the early years of my studies in political science, I began engaging with photography which led me to continue to film studies. Following a non-linear academic path, I discovered that my interests often lay at the intersections of the fields I was studying. The way history and its dominant narratives are constructed is very similar to how a creator tells a story through cinematic narration. The resemblance lies in power, specifically, the control one has over the construction of a story—what is included and ultimately what is excluded from it.

The immediacy of the photographic medium allows me to construct and narrate stories from a familiar and personal creative space, while also giving me the freedom to fluidly navigate between the visible and the invisible, suggestively using elements of reality.

SW: How would you describe the main questions that drive your work? How do they show up in this project?

EA: I tend to gravitate toward the uncomfortable truths and contradictions that challenge established narratives. Rather than seeking themes with a neat, clear purpose, I focus on absences, gaps, and transitional spaces and states. In my ongoing project Didn’t Mean to Keep You Waiting, I explore questions around illness and stigma, the right to control our own life and death, and the way individual and collective memory shapes our perception of the world. I see personal, political, and existential themes intersecting in my work, but what drives them all is a deep curiosity—and an underlying restlessness—about whether, and how, we can communicate the complexity of human experience to others.

SW: Didn’t Mean to Keep you Waiting reanimates a story from the early 20th century. Can you tell me a bit about this narrative and the starting point of the project?

EA: The motivation for creating this work arose from the research conducted by the Academia Romantica, an experimental learning and interdisciplinary structure based on primary research attempting to penetrate and transcend traditional fields of artistic discourse, who had collected 200 suicide letters from 1821 to 2021. Through an open call in 2020, each participant was assigned a letter to create a work based on it. The idea for my photographic project was born from fragments of a suicide letter that was published in the press as part of a police report.

SW: Tell us more about this fragment that caught your attention.

EA: Stylianos Balmetakis was a teacher on the island of Folegandros—part of the Cyclades chain—for six years between 1895 and 1901, where he fell ill with tuberculosis. In 1901, he was hospitalized at the Municipal Hospital of Athens for a month, and during this time, his health deteriorated. He made a conscious choice not to return to his family and students, ending his life in one of the city’s central hotels. My initial intention was to find a language using photography to address this act that so often leaves us awkwardly silent when confronted with it and to create a space for free reflection around it.

SW: What drew you to work with the story and connect it to the present?

EA: Beyond the intrigue of this collective project that seeks to create something new from these suicide notes, I was initially drawn to the deeply personal way in which illness shapes our relationship with society. The teacher’s tuberculosis and eventual suicide are not merely a tragic personal narrative, but a reflection of broader moral dilemmas and inner conflicts. Balmetakis’ choice to end his life, believing his failing health had made him a burden, offers a profound commentary that carries as much societal weight as the choice to endure and remain part of the community.

I encountered this story early during the COVID-19 pandemic at a time of great uncertainty. We were all experiencing deep isolation and detachment from the social fabric, while also facing an intensified sense of individual responsibility for the potential transmission of the disease to those around us. The personal experience of isolation and the responsibility I felt, as did many others, to protect those around us brought new questions to the surface and allowed me to relate the teacher’s story to this contemporary context. The illness itself, the sense of exclusion and grief, and the weight of responsibility—both for ourselves and for others—create a connection between two eras, giving Balmetakis’ story a haunting resonance. The project reveals the timeless human condition of what we do when faced with the unknown.

SW: The project mixes—among others—archival material from the school on Folegandros with photographs you’ve made now. Can you talk about this tapestry of images?

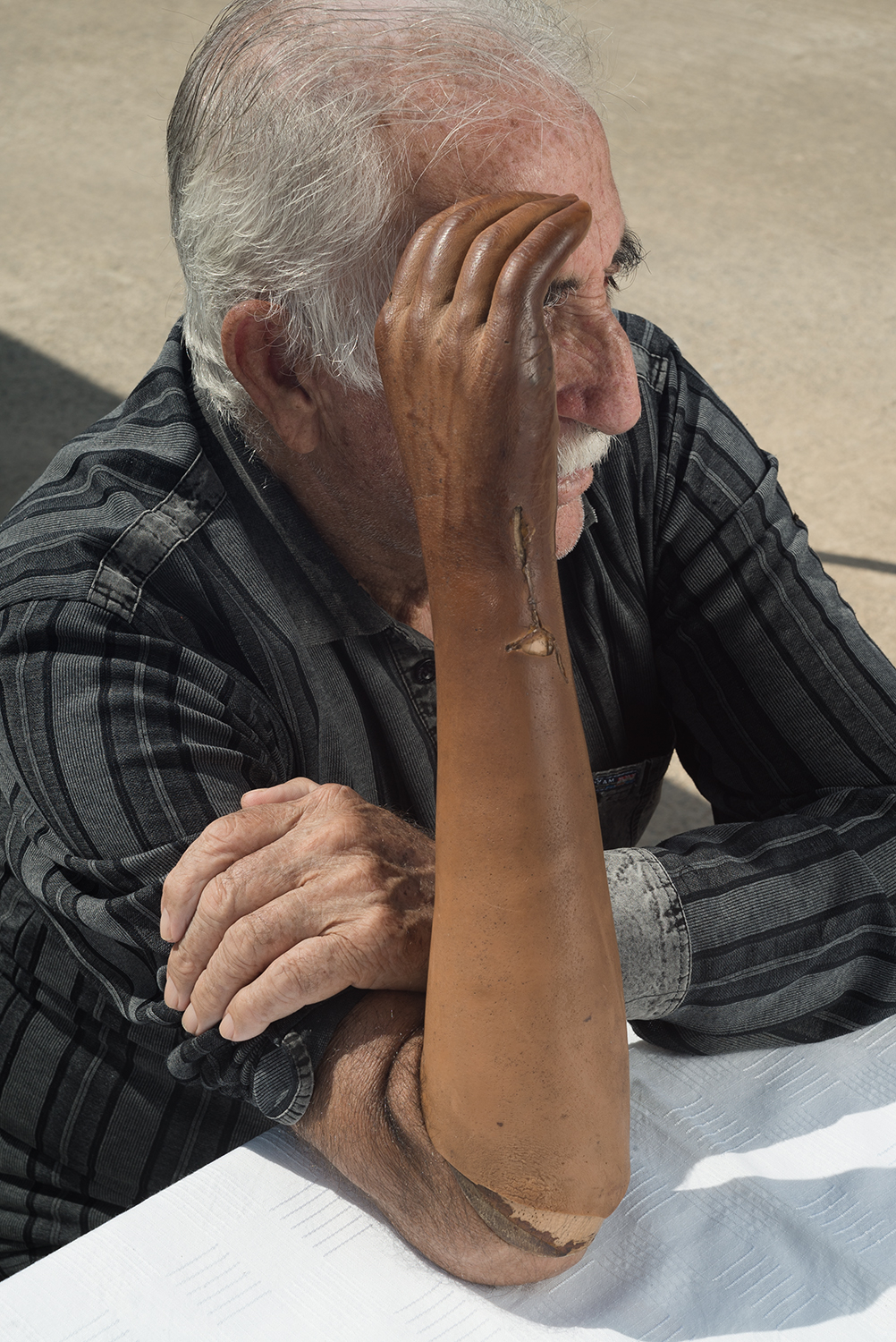

EA: Further to the traditional methodology of searching for such sources in public records that could be included in the project as visual elements, during my visits to Folegandros I’ve wanted to connect with the island’s current residents, particularly the elderly, who may be descendants of those who knew the teacher. As someone carrying a story that once belonged to the collective memory of the community that has since faded, I feel a sort of obligation to return this forgotten knowledge. I’ve been collecting oral testimonies and inviting its members to recall information from family and communal archives focusing mostly on photographic material—both about the era and the themes of the project but also about the individuals that I work with—in order to support the broader context and production of new images.

SW: You’ve previously spoken about the incompleteness of dealing with a narrative whose author is no longer present. How did you navigate translating this real, and rather sensitive story of suicide, into fiction? What were the challenges you encountered?

EA: The incompleteness of the story feels both challenging and liberating, setting limitations yet giving me a sense of creative freedom. I am fully aware of the ethical weight of working with a real person’s intimate story, especially knowing how little of his whole story I can uncover due to the distance in time. Rather than attempting to reconstruct the events, I embraced high abstraction and fiction as ways to personally deal with the absence and missing parts.

I created a metaphorical narrative that combines clues, symbols, and directed scenes around the character. These images aren’t exactly ‘about’ Balmetakis, but rather echo his experience. Throughout the building of the series, I carefully navigated my own sense of responsibility, constantly negotiating how much of his story I can ethically include without overstepping into appropriation.

SW: What questions did the story raise for you?

EA: Upon reading the police report, it became clear that the story extends far beyond the facts presented. The narrative gaps and mystery surrounding Balmetakis’ inner motivations raised numerous questions, drawing me in both visually and conceptually: the social dimensions of illness, the act of suicide, memory (both individual and collective), decay, the disruption of the body and matter, the interplay between life and death.

These themes led me to explore in a multi-faceted way the act of suicide not as a finality, but as a form of communication—a way to reach others rather than an absolute end. From this understanding arises an urgent need for reflection and creation around the following question: How can we confront the absurd and shape an experience of the world that is open to both its beauty and its brutality?

SW: A striking part of the project is its visual language, which both leans on the aesthetics of evidence and an uncanny surrealism. Can you tell me about the creative decisions behind these choices?

EA: I seek to balance the tangible with the intangible. The aesthetics of evidence—such as archival documents and artifacts—serve as anchors, providing authenticity and a sense of historical context to the lived experiences that inspire my work. The surreal elements and staged imagery allow me to transcend the limitations of linear storytelling, crafting scenes that are both rooted in reality and rich in metaphor. Since my images are produced over short, specific periods between months when I cannot travel, I take the time to observe and mentally envision the pictures I need to advance my narrative.

SW: Can you elaborate on the title of the project?

EA: The title concerns the reviving of a narrative lost to time, reconnecting and communicating with a figure whose life and death have not been marked in history and collective memory in an effort to make sure that his existence is not forgotten.

On the other hand, Didn’t Mean to Keep You Waiting is my imaginative interpretation of Balmetakis’ mental condition and the emotional space he may have inhabited while deciding to end his life, leaving his students and family in a state of ‘waiting’. This phrase, for me, encapsulates his emotional weight, not explicitly expressed in his suicide letter, but mostly felt through the silence and the aftermath he leaves behind.

Lastly, it speaks to the expectation that one might have in searching for answers, only to discover that the narrative, instead of providing clarity, offers more questions mirroring the open-ended nature of life and death, pushing us to reflect more deeply on the gaps between what we think we know and what remains elusive.

Editor’s note: Eirini Androulaki was a winner of LensCulture’s Critics’ Choice Awards in 2024. Be sure to check out all of this year’s winners.