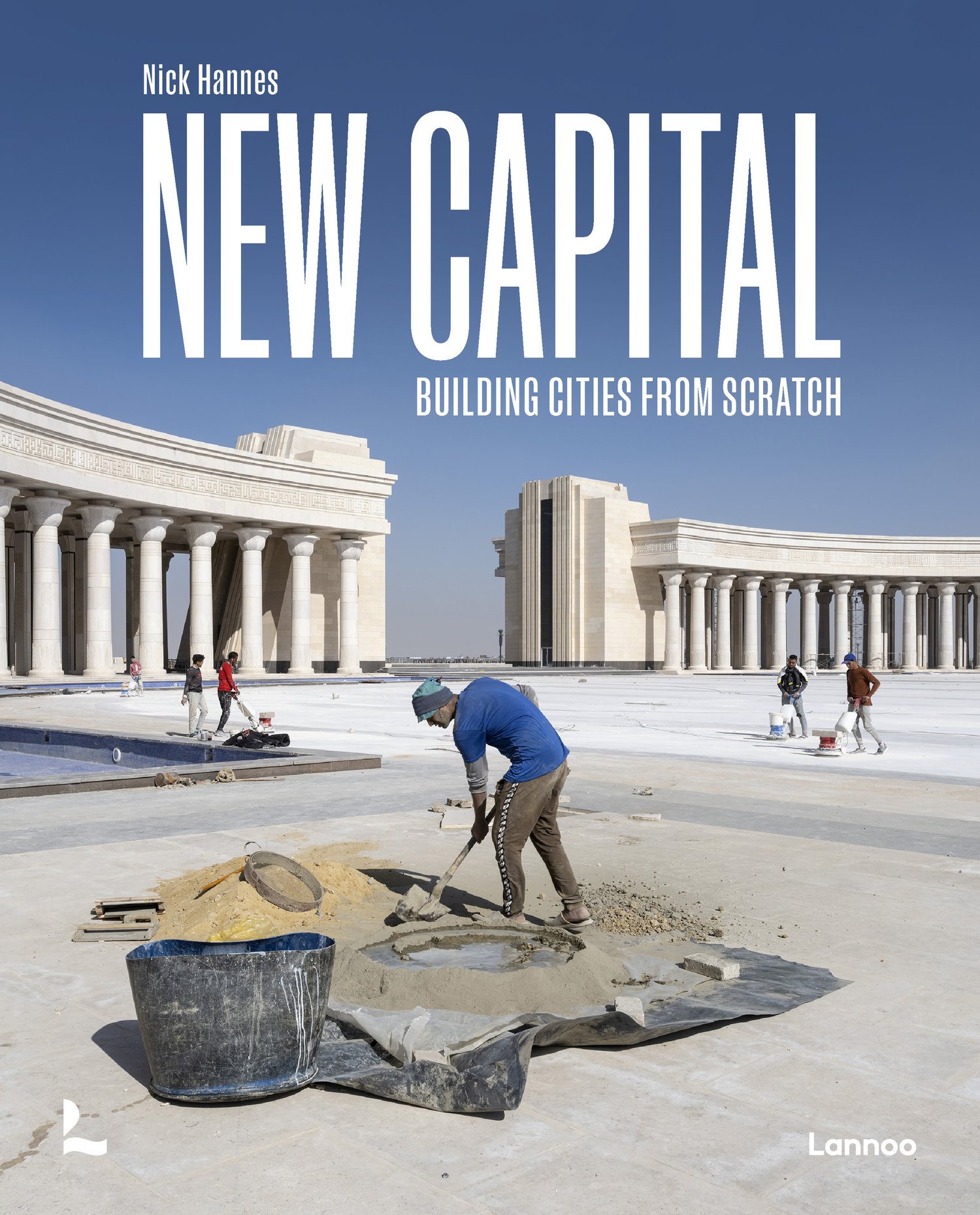

What does a city built from scratch look like? In theory, it’s a chance to create a utopia that respond to the social, economic and environmental challenges of the time. As Nick Hannes’ book New Capital reveals, the reality proves to be much darker. Travelling to six different capital cities across the world, the Belgian photographer explores the bizarre phenomenon of the ‘trophy city’—bombastic, man-made environments born and shaped by the patriarchal forces of political power and control.

Opening with Brasilia, a city inaugurated in 1960, and ending with Nusantara, the new capital of Indonesia that was still unfinished at the time of the book’s publication, each city was created by its nation state with a specific purpose in mind. And yet the environments Hannes documents with his wry, outsider eye seem more similar than they are different: shiny and grandiose cities with poor planning that the writer Dorina Pojani describes as “without history” in the book’s introduction. Far from liveable, these generic capitals are disconnected from the local, founded on image rather than the needs of the population that inhabit them or the ecosystem they belong to.

In this interview for LensCulture, Nick Hannes speaks to Sophie Wright about the interconnectedness of his projects, the global phenomenon of the ‘generic city’ and using humor as a strategy to engage his audience.

Sophie Wright: How did you come to photography and what has kept you there?

Nick Hannes: My father had a camera that I experimented with as a teenager, in the late 80s. Later, I installed a darkroom in my grandmother’s bathroom. I think I was just lucky to find a hobby that suited me very well. Later, when I started studying photography at the art academy in Ghent, things got more serious. We were encouraged to go outside our comfort zone into the city and connect with strangers. Now, more than 30 years later I still do that. Photography is a fantastic activity for curious people. It takes me to places I would otherwise never go, and to people I would otherwise never meet. It gives meaning to my life and intensifies the journeys I make.

SW: How would you describe the main themes that drive your practice? When did you become interested in architecture and its influence on us?

NH: My photography reflects on contemporary themes such as migration, globalization, urbanization. It doesn’t focus on individual stories, but rather looks at the bigger picture, how we humans shape our world—and sometimes destroy it—and how we relate to our environment. A lot of my motivation and choices of subjects come from my concern about the social and ecological state our world is in.

Urbanization has always been an underlying theme in my work. My first book Red Journey, that I published in 2009, already includes photographs of alienating urban landscapes in cities such as Astana in Kazakhstan and Ashgabat in Turkmenistan. Later, during my travels along the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, I turned the camera to tourist infrastructure in Spain which has a huge impact on the natural landscape and local communities. Further research took me to Dubai—perhaps the most excessive example of high-speed neoliberal urban development—in which making profit seems to be the main goal.

SW: What was the seed for New Capital? What drew you to the topic?

NH: My projects are thematically linked: one follows organically from the other. New Capital is a continuation of the theme I dealt with in Garden of Delight; a project I made about Dubai. Rather than a well-balanced and sustainable society, Dubai is primarily the product of pervasive profit-seeking. Social fabric is secondary to image, status and urban spectacle. Entertainment and consumerism supplant art and culture. People meet in simulated mock worlds such as theme parks and shopping malls, where an obsession with surveillance and control stifles any form of spontaneity.

Dubai is not an isolated phenomenon. The city inspires rulers and city-planners worldwide. The ‘Dubaization’ of society is in full swing. To delve further into the subject, I turned my focus to six new capitals. These are cities that did not grow organically over the centuries, but were built at lightning speed from scratch according to a pre-designed master plan. In theory, new cities built from scratch provide the ultimate opportunity to create a perfect utopia. Unfortunately, these capitals were not built to meet the needs and desires of the population, but rather to perpetuate political power and cater to the rich.

SW: What were your criteria for choosing the six cities you photographed?

NH: I selected six new capitals in three continents, since it is a global phenomenon. You can roughly divide them into three generations. The oldest example is Brasilia in Brazil, founded in 1960. Abuja in Nigeria and Astana in Kazakhstan were inaugurated in the 1990s. The most recent cities are Sejong, Korea, the New Administrative Capital of Egypt (NAC) in Egypt, and Nusantara, Indonesia. So there is variation in geography as well as age.

SW: The countries these capitals belong to are wildly different in their cultures, histories and customs—so much so that you might expect their capital cities to capture their unique characteristics. But they all share features that echo what Rem Koolhaas the ‘Generic City.’ What were the unifying ‘generic’ elements or issues you came across?

NH: The new capitals are cities from which the human dimension has disappeared. They are mostly monumental and prestigious cities boasting interchangeable spectacle architecture, but they lack identity, local character and a lived-in socio-cultural fabric. Shopping centers and shopping streets seem to be copies of each other. These cities usually take up a lot of space. City planners did not have to hold back because there was plenty of room.

The only capital that is less monumental and has more of a human scale is Sejong in South Korea. It is a circular city with a green center and an efficient public transportation system. The relationship between city and residents seems more balanced there. Making this project I realized all too well that it is impossible to build a city in a few years. It takes many generations for a city to mature—let alone acquire a soul.

SW: The book really wonderfully captures this tension between the ‘ideal’ capital city and its dystopian reality. Were you surprised by what you encountered on the ground?

NH: Every trip is well prepared. Research on the subject and the destination is crucial to making content choices. I usually have a clear idea of what to expect in terms of images when I leave on a trip. That’s why there are no big surprises. But the first impression of a city I have never been to before can be overwhelming. The first day I barely take pictures. I need to acclimatize, get used to the new environment, culture, sense how people react to my presence and to the camera. It’s a matter of building enough confidence and getting myself in the right mood, before starting to work.

SW: Across the board, the architecture of these new capitals is bombastic and monumental. What kind of relationship to the environmental crisis do these cities have?

NH: At a conference for urbanists last year in Turin, I heard a speaker say, “The most ecological city is the one that is not built.” As a rule, it is better to densify existing cities and make them sustainable and livable, rather than sacrifice even more open space. Except for Sejong in South Korea, the new capitals I visited are car-based and widely laid-out. The New Administrative Capital of Egypt is a Dubai-inspired city in the middle of the hot desert. Nusantara is envisioned as a “green and smart forest city,” but the local economic activities—(illegal) coal mines and large-scale palm oil and eucalyptus plantations—are not exactly environmentally friendly.

SW: How did you navigate your photographic explorations of each city and what were you on the lookout for? What was your work process?

NH: All my travels are a combination of thorough research, comparable to a location hunter for films, and improvisation or chance on the spot. Before I leave, I make a day-by-day schedule of places, buildings, neighborhoods I want to photograph. I try to arrange as many shooting permits in advance as possible, so as not to lose precious time when I’m abroad. Interesting urban landscapes or architecture often form the backdrop for my photographs. But usually it’s not sufficient to create a layered photograph.

Once on site, I wander around, from morning to night, looking for coincidences, unexpected situations and encounters. It’s all about probability. The further I walk, the longer I am on the road, and the more time I invest, the bigger the chance of bumping into an exceptional situation or event. This way of working, where I have no control over what can happen, is intense but at the same time very rewarding when it succeeds.

SW: How important is humor in your work?

NH: Humor and irony are important components of my photography. I think humor is a very useful tool to get people’s attention, especially when dealing with serious topics. It’s part of my visual strategy to entice people to look at , and then hopefully further reflect on, what the image is really about. It’s not just a stand-alone visual gag, as we sometimes see in classic street photography. It serves a meaning.

SW: In many of these cities there is a jarring contrast between wealth and poverty. Did you meet any proud citizens?

NH: It is true that most of these cities encourage social segregation. While the inner city is inhabited by the upper middle class and the wealthy, less fortunate citizens are pushed to the periphery. So it depends on who you are talking to. I met proponents and opponents in just about every city. Opinions are more pronounced in the more controversial examples like the Egyptian and Indonesian new capital.

SW: There was quite a range in the lifespans of these cities. Was there a noticeable difference in character between the older cities and the newer ones?

NH: Brasilia is now 65 years old—and the novelty has long since worn off. Although the architecture of Oscar Niemeyer is timelessly elegant, the urban sprawl is similar to the more recent capitals I photographed. While Brasilia was supposed to become an egalitarian model city back in the 60s, Astana and the New Administrative Capital of Egypt are very reminiscent of neoliberal Dubai, with an urban development based on prestige, nationalistic symbolism and ‘starchitecture.’

Nusantara’s government area is monumental as well, with a giant presidential palace to radiate power and pride. The rest of the city remains to be seen, as construction is still in its early stage. And, after more than 40 years of construction, Abuja is still not ready yet. Within the inner city center, vacant plots of land have been taken over by farmers and shepherds which results in a strong visual contrast between the big city and rural life.

SW: How difficult was it to get access? Are these places very restrictive in terms of what you photograph?

NH: Astana, Brasilia and Sejong were easy to visit on a tourist visa. In Abuja I hired a fixer for safety reasons. I usually work in the public area, and that involves risk in a country where jihadists and criminals carry out kidnappings and extortion. In Indonesia and Egypt, official permission from the authorities was needed, to get access to the sites where the new city is being built. Egypt was a long and frustrating procedure as the defense ministry had to issue a permit. In the end they granted me a measly four days to explore the city, even though I had applied for two weeks. But it turned out well. It even earned me the World Press Photo Award for the Africa Stories category in 2023.