To take a peek into someone else’s notebook is a rare pleasure. For those that partake, scrapbooking or journaling can be a way to orient our humble journeys through time and space; a small and habitual way of making sense of the day/week/month/year. What you do with your notebooks is another question. Perhaps they serve a temporary, practical purpose. Or an archival one, gathering dust stacked up in a cupboard, patiently awaiting perusal by future generations.

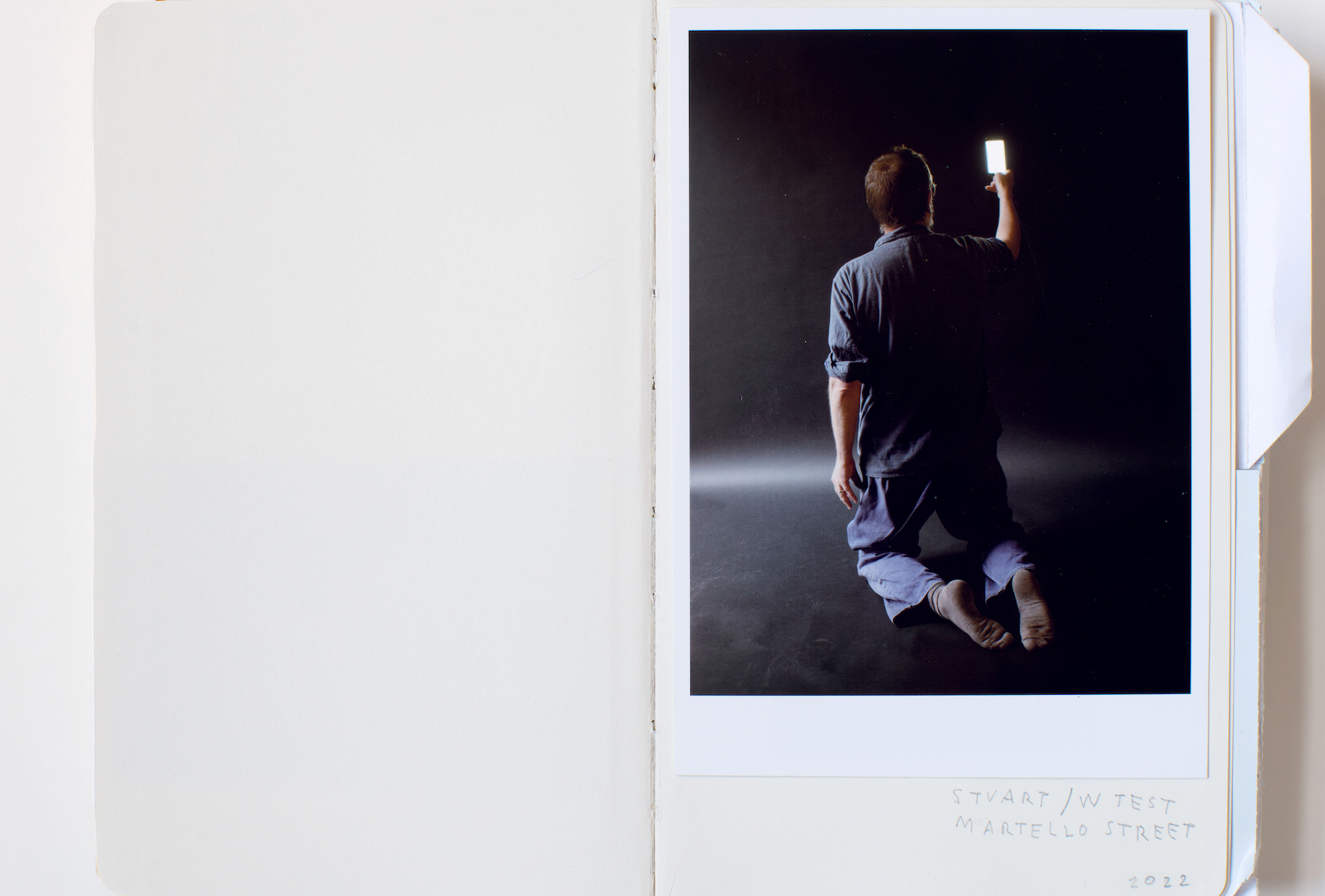

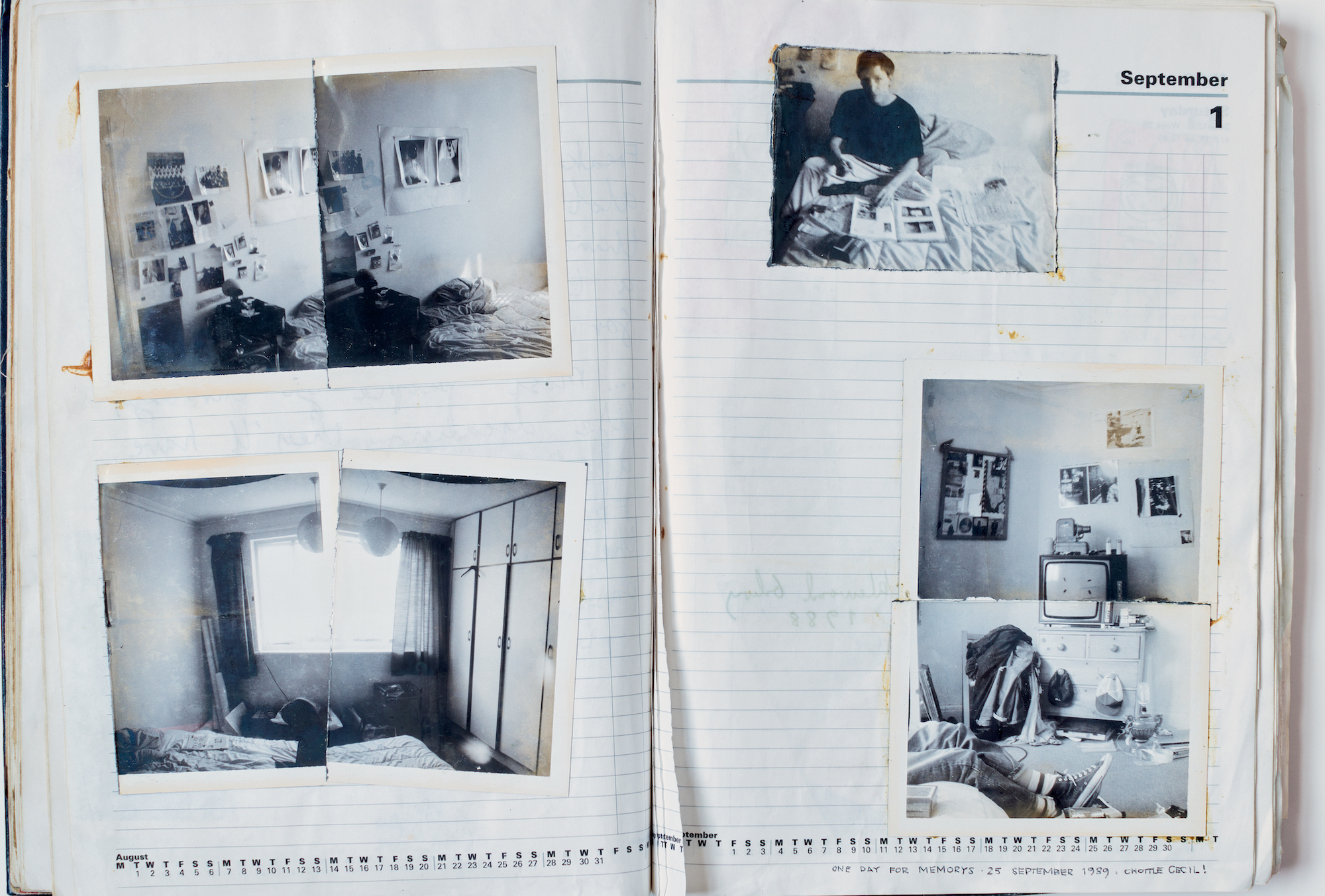

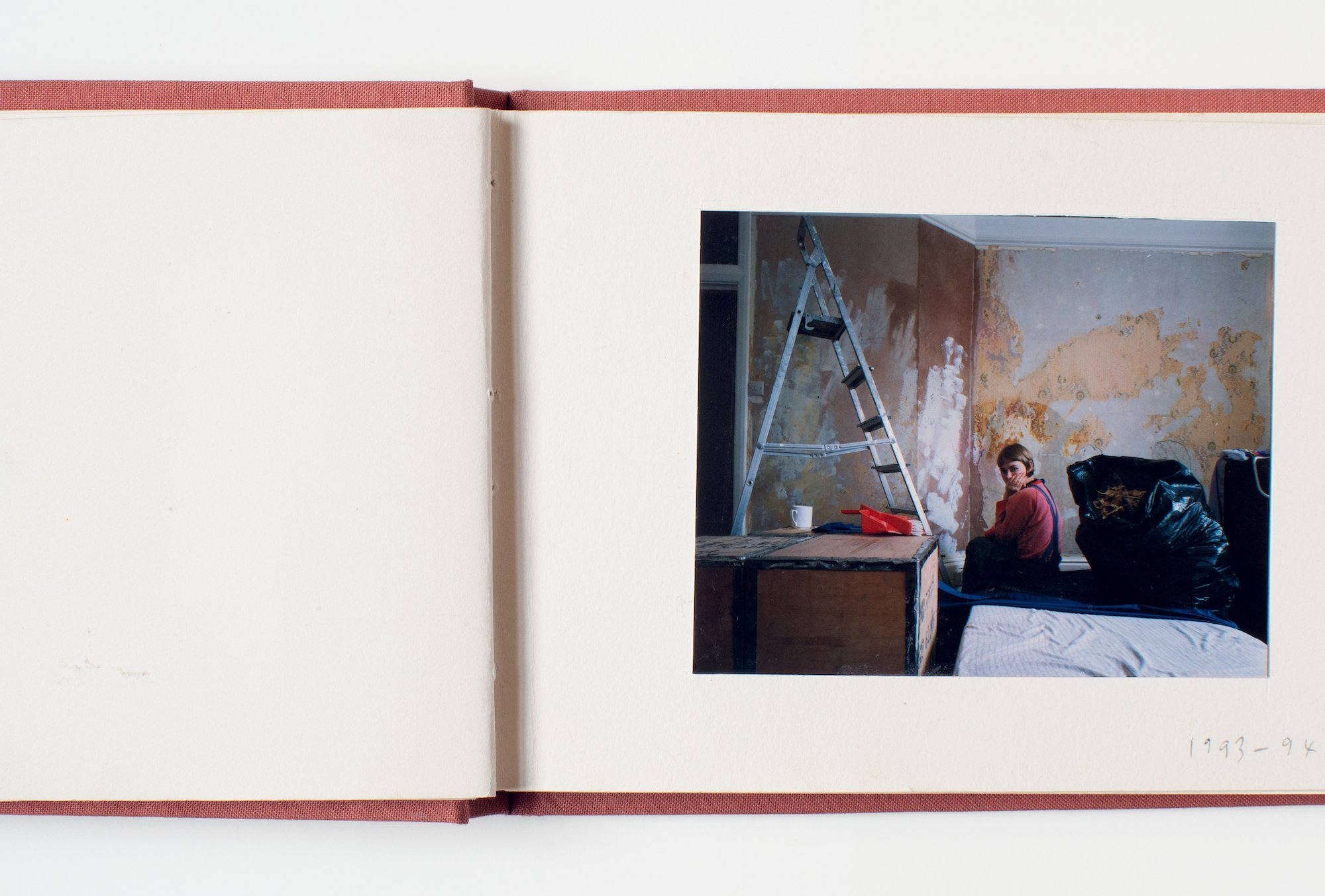

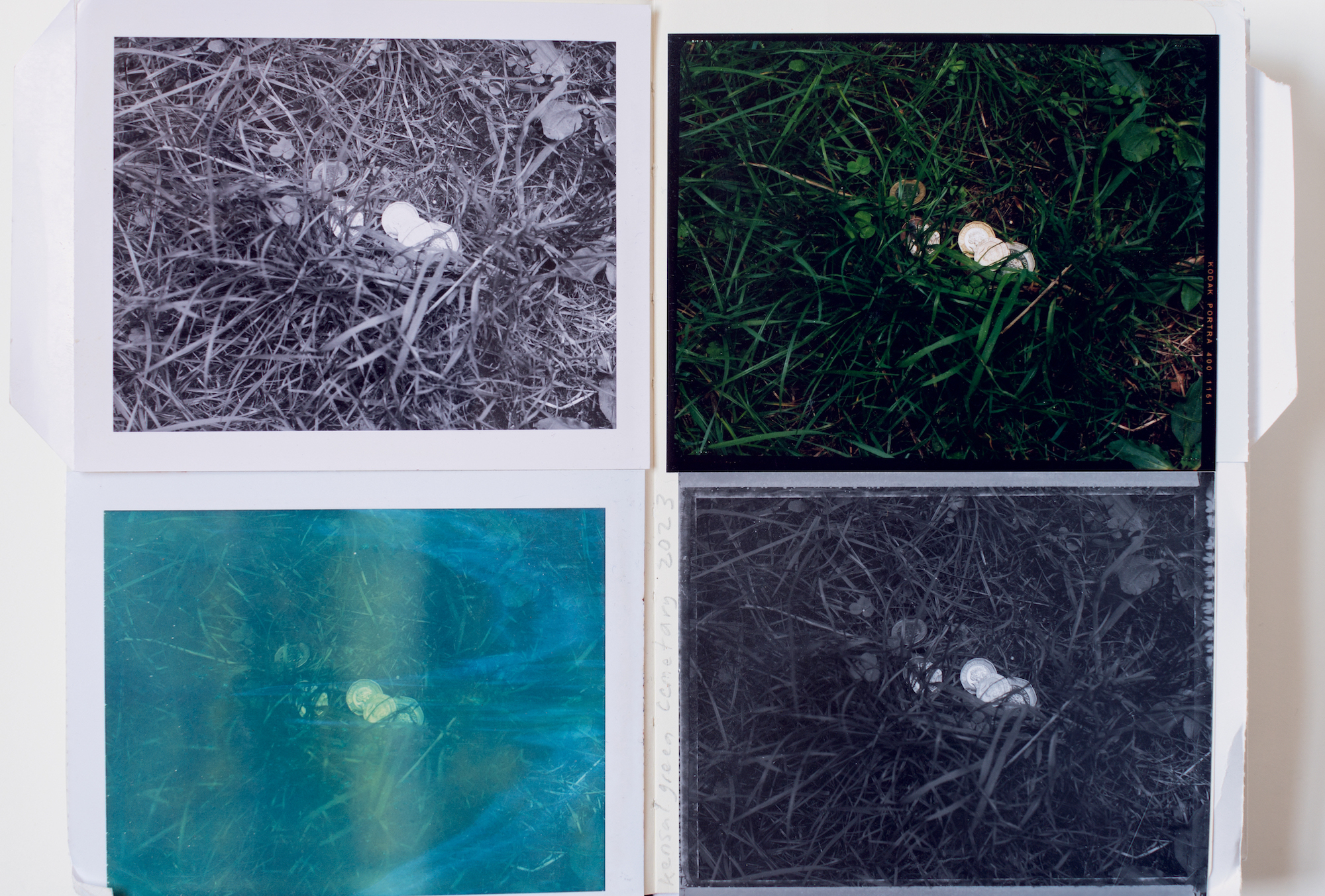

One of the most satisfying aspects of Workbooks by Nigel Shafran is the continuity that emerges when notebooks are threaded together—four decades worth of these black leather bound books are put to work, morphing from a pile of contained experiences into an animate object that records the British photographer’s life through doodles, images, writing and other bits and pieces.

Shafran has had a long and fruitful career, perhaps known most as a renowned but reluctant fashion photographer making radical work in the 80s and 90s, but also as a book artist, finding balance from the shiny world of fashion by focusing on the most commonplace of things. Though in many ways Workbooks charts this career, it is not really about ‘work’ as much as it is about life; the process of navigating different cities and their mutations, the realities of becoming/being an artist and the joys of building a family.

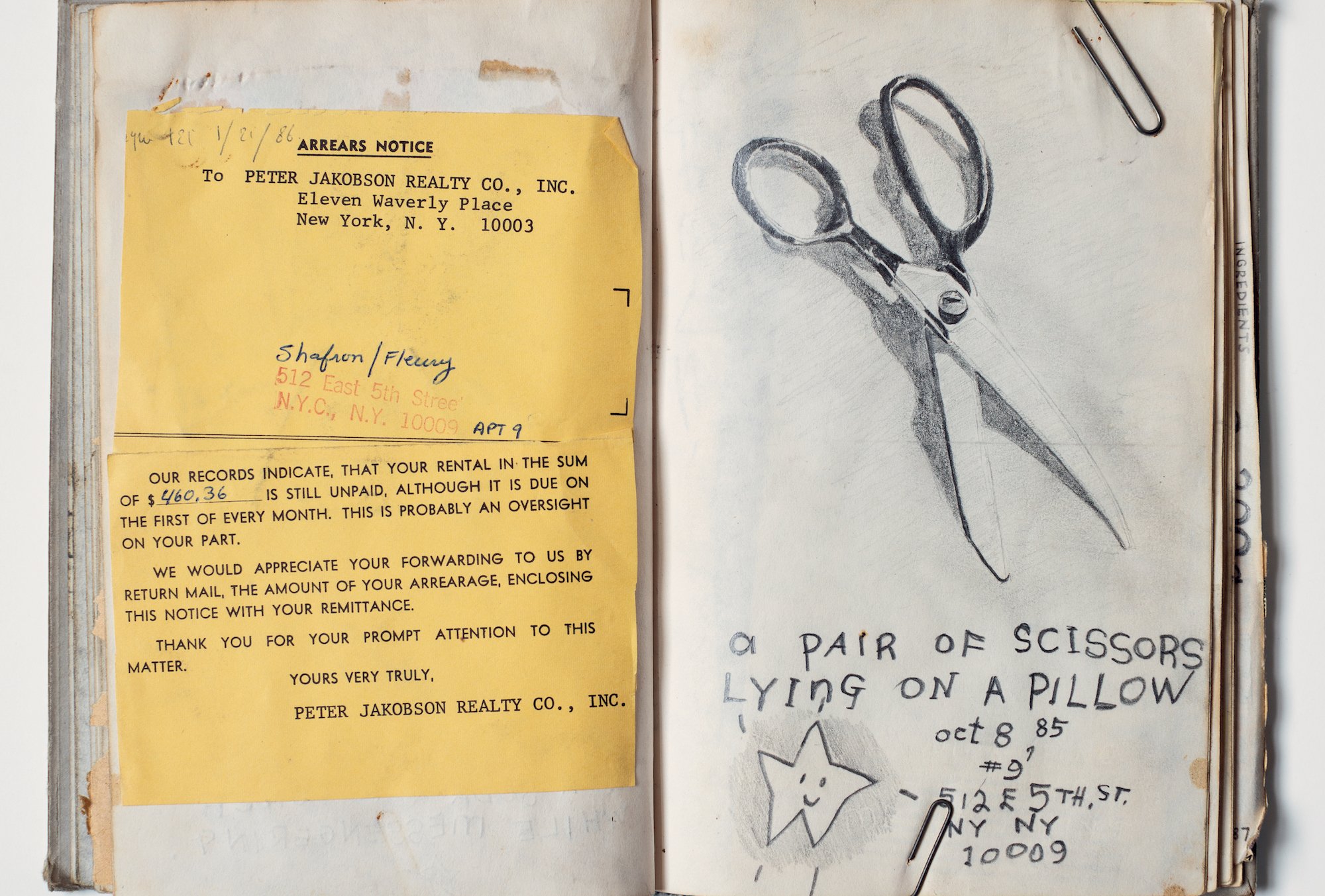

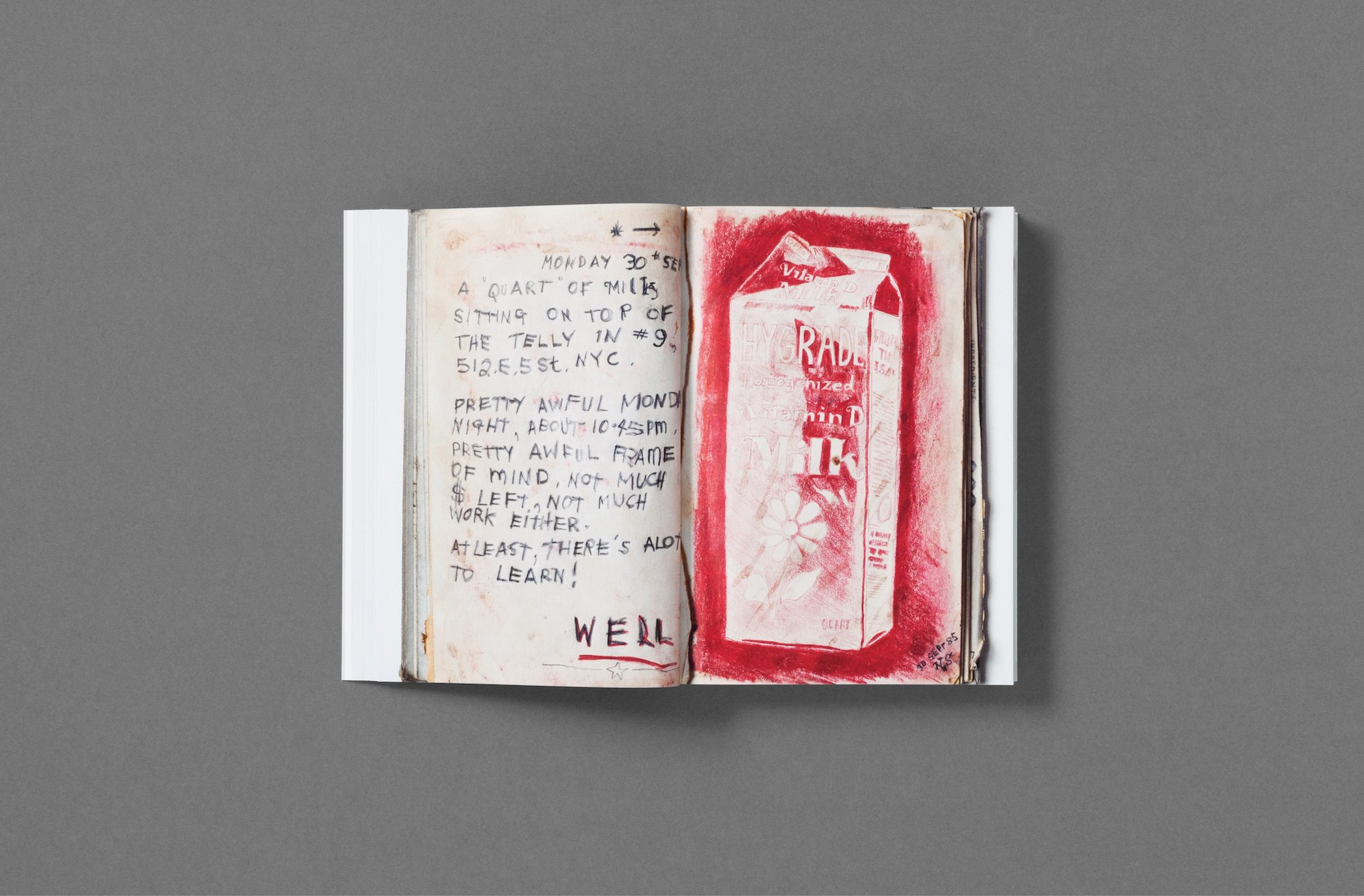

The book opens with Shafran’s grubby beginnings as a photographer, assistant and bike courier in New York City. Cutting through the mystique of the fashion world, we see the boredom of waiting for castings, the young photographer fooling around at the studio before the model stands into shot and an arrears notice for unpaid rent. A diary entry from some time in the mid-eighties reads: “Pretty awful monday night, about 10.45pm, pretty awful frame of mind, not much $ left, not much work either. At least, there’s a lot to learn.”

For Shafran, beauty is to be found in the ordinary, not in the high glamor of his work world. At some point a new chapter of his life opens back in London. His partner Ruth appears—who fans will recognize from Ruthbook and Ruth on the Phone—and they build a domestic life together. Later a son, Lev, enters the pictures. The kitchen sink becomes a subject, dishes in the drying rack lovingly observed. The clutter that makes up a home receives the same attention, sometimes in his own house but also out in the world like in the cluttered treasure troves of charity shops.

Respecting the unruly laws of the notebook, the publication casually flows through time and space, from home to city life, inside to outside, not stopping to intervene nor reflect aside from a short introduction by David Chandler. A repository for this avid collector and his many street finds, its content pieces together the story of Shafran’s varied interests. In previous interviews, the photographer has expressed discomfort with explaining his photographs. “The work is the work.”

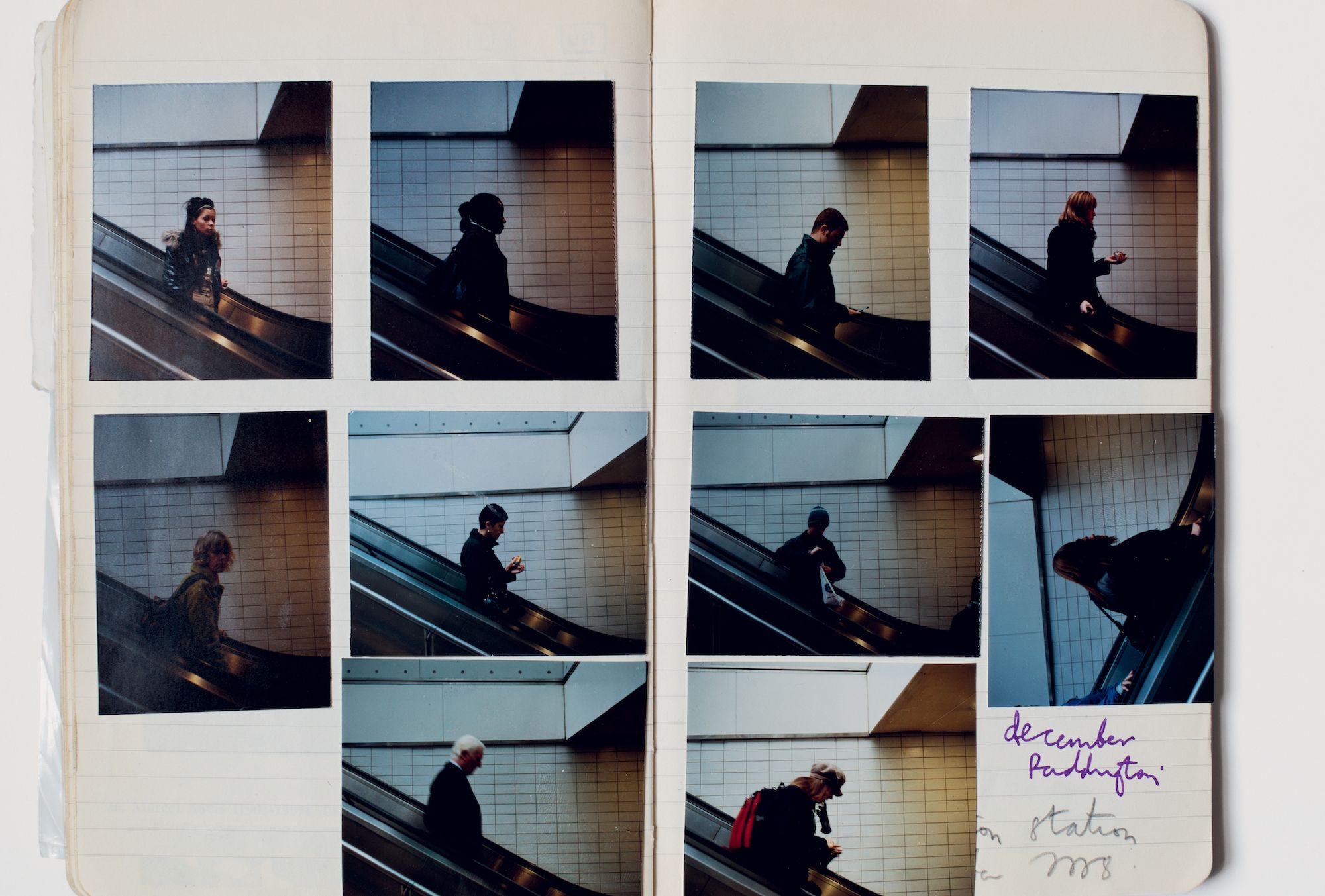

It is in the devoted repetition of certain objects and items that we get a sense of what is important to him. This includes, but is not limited to: phones, stairs, crisp boxes, check out counters, compost, deliveries out on the street. And family. Mass consumption crops up all across Workbooks, perhaps informed by the photographer’s commercial work but also just by being a human living, and spending, in a city.

With a soft spot for supermarkets, Shafran sensitively photographs sandwiches—and their empty packaging post-gobble—self-checkout screens, British staple grocery stores Tesco’s and Sainsbury’s from the outside, employees on the inside (a note alongside reads: “people are the soul of the supermarket”). There are drawings of sofa adverts and, later on in the book, the photographer even appears dressed as a petrol pump, posing at Sainsbury’s.