A book, much like a boat, can take you places, bobbing along on a narrative that pitches and crests like the sea. With a neon yellow spine resembling a ship’s keel, Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo’s book, El pez muere por la boca (The Fish Dies By Its Mouth), brings readers to coastal communities of his native Colombia. With each flip of a page the keel moves, advancing the story along, moving from images that feel documentary to ones that play with magic realism, casting a spell. Centering on those resisting the pressure of drug trafficking and holding onto their own culture and resilience, Escobar-Jaramillo’s ambitious project defies easy categorization.

In recent years the world of photobooks has exploded. Book fairs have sprung up everywhere, from multi-day stretches with VIP hours to scrappy upstarts staged in gyms and artist spaces. But with this has come an understandable glut. Many photobooks stick to the form of monographs or glorified portfolios of a project. Rare is the book that takes the challenge of its format and runs wild.

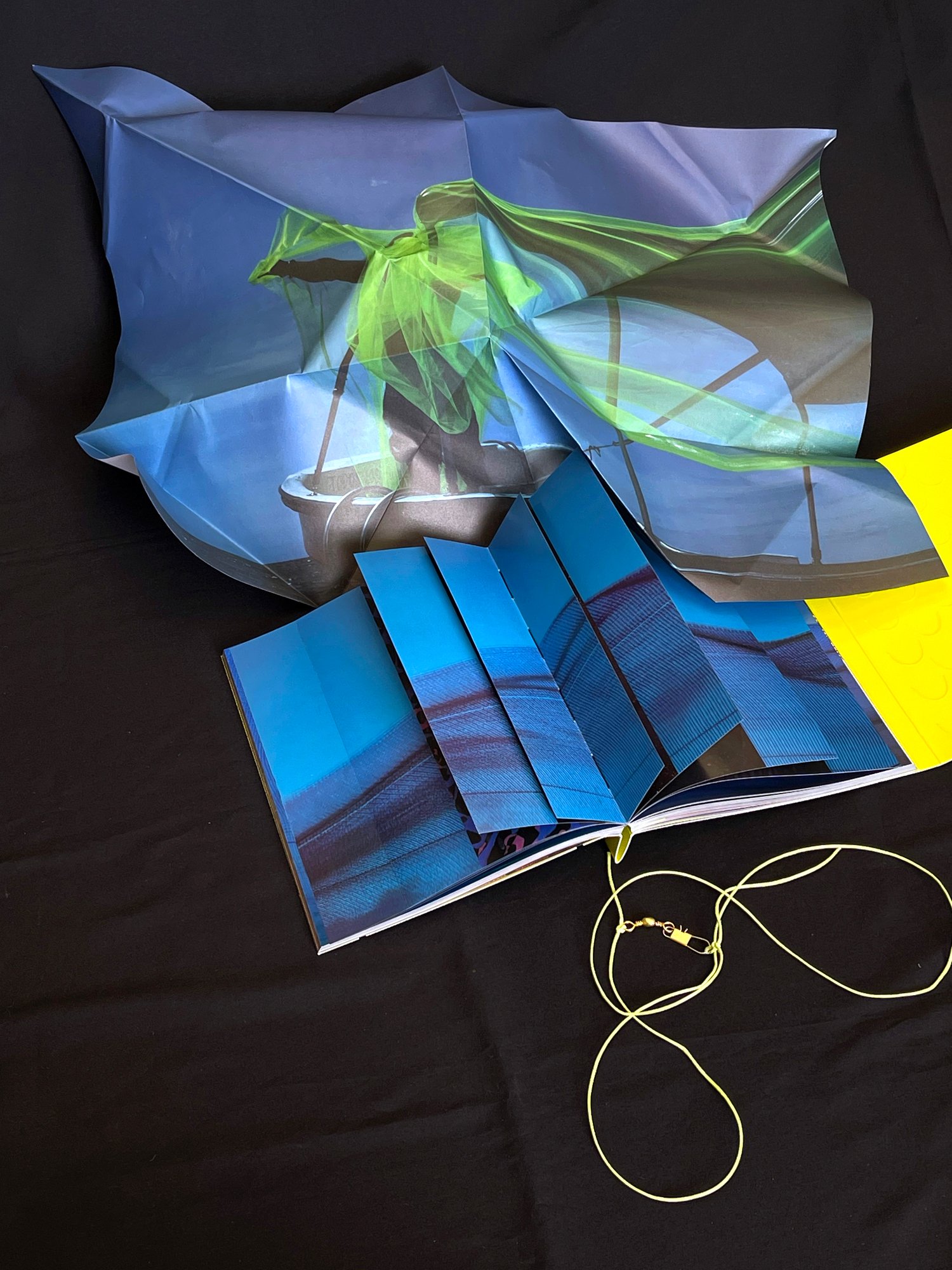

Escobar-Jaramillo is one of the exceptions; El pez muere por la boca blows up the staid concept of a photobook. He has created a living, breathing, transformable object. Every detail extends the narrative—from a cover with pop-out fish scales, coaxing the viewer to see what exists behind them to a spread of the ocean that reveals in flippable sections what lies beneath the sea. This theme of interaction as well as the push to look deeper imbues the book with Escobar-Jaramillo’s ethos that one must look beyond easy perceptions.

A lazy perception of Colombia is tied to the history of drug trafficking—even though the rate of drug consumption in the country is dwarfed by numbers in the US and across Europe. For many years, the country was the world’s leading producer of coca, causing violent ongoing conflict between the government and various narco paramilitary organizations.

“Photographers were always documenting the horrors and terror. I prefer to work together and create new imagery, not only thinking about the past and the horror and pain but also trying to look forward to new possibilities,” Escobar-Jaramillo explains. With this in mind, he returned to his past, in this case to the coastal community of Rincon del Mar, on the Caribbean Sea, where he spent many summers as a child. It had been over a decade since he had last returned. When he asked his uncle why, he explained that for years dangerous paramilitary groups controlled the area. Shortly after, he went fishing on a boat with family. Floating on the sea was a package. The boat’s driver told them it was cocaine called ‘pesca blanca’ the white fish.

When pursued by the Colombian navy, drug traffickers on both coasts, the Pacific and the Caribbean, will dump their cargo overboard to lighten their boats to make a speedy escape. As someone in one of Escobar-Jaramillo’s accompanying video works says: “The white catch is all about opportunities.” These packages are at times found by local fishermen who must decide if they should ignore them or pick them up, using them to buy a new boat, construct another floor of their house, throw a party, or make something out of the surprise circumstances. For others, the temptation is not there. They have no desire to become a link in the chain or they have already lost relatives to drug violence or simply have no desire to be involved in illegal activity.

He began thinking about strategies to tell this story and challenge the blinkered view that people have of Colombia. The first is a continuation of his expansive approach to photography. At times, images are brought to life through augmented reality technology. Scanning a page with a phone brings up an animated GIF of legs dancing, a woman in motion, or tropical fruit multiplying. The imagery leaps off the page, immersing the viewer in a scene. There are stickers in the back, a fold-out poster print, and video works that exist alongside the book as well.

The second strategy is one of participation, involving rather than simply documenting the community. The book captures the everyday whilst building a language of magical realism that transports readers. “The project is playful, it’s colorful, it has satirical comments and metaphors. I want people to catch up, to look from a different perspective,” Escobar-Jaramillo explains. This other perspective enforced the need to work with the community. He elaborates, “It’s very important to create these images with them, it is a way to collaborate. We are used to this idea that photographers are the ones completely in control. What happens if we photograph with them? If we include them in our themes, our ideas, with their thoughts, their dreams, their fears? I think it could make our photographs a little bit richer.”

The book reflects a dialogue. Escobar-Jaramillo began to make and pair images in conversation. In one arresting combination, a young boy lies down, eyes covered with distorting glass and mouth open. On the facing page, a fish hook glistens in the sunset. In another image, a hand holds a gun, or rather that is what one might first read until a second look reveals it to be a piece of coral. Fishermen appear throughout, their faces hidden. A cinematic bolt of lightning illuminates a gathering. A wall of white-sheeted packages commands attention on an empty beach, mangroves trail into the water behind. Is this a monument or an overly ambitious haul, a sleight of hand or a dangerous find? Throughout the images, the community dazzles with their creativity, celebration, and ingenuity constructing scenes as they navigate and push back against outside pressure.

In El pez muere por la boca, Escobar-Jaramillo succeeds in getting the viewer to not only look again but to touch and listen, opening up an often overlooked world. “It’s like this idea, when you look at the sea you see a beautiful line on the horizon and we think that that is the world, that what we see is what we get,” he says. “But underneath, there is a world of new life, new possibilities that we haven’t discovered yet.”

Editor’s Note: Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo was a finalist of the LensCulture Art Photography Awards 2024. See all of the winners and finalists here.