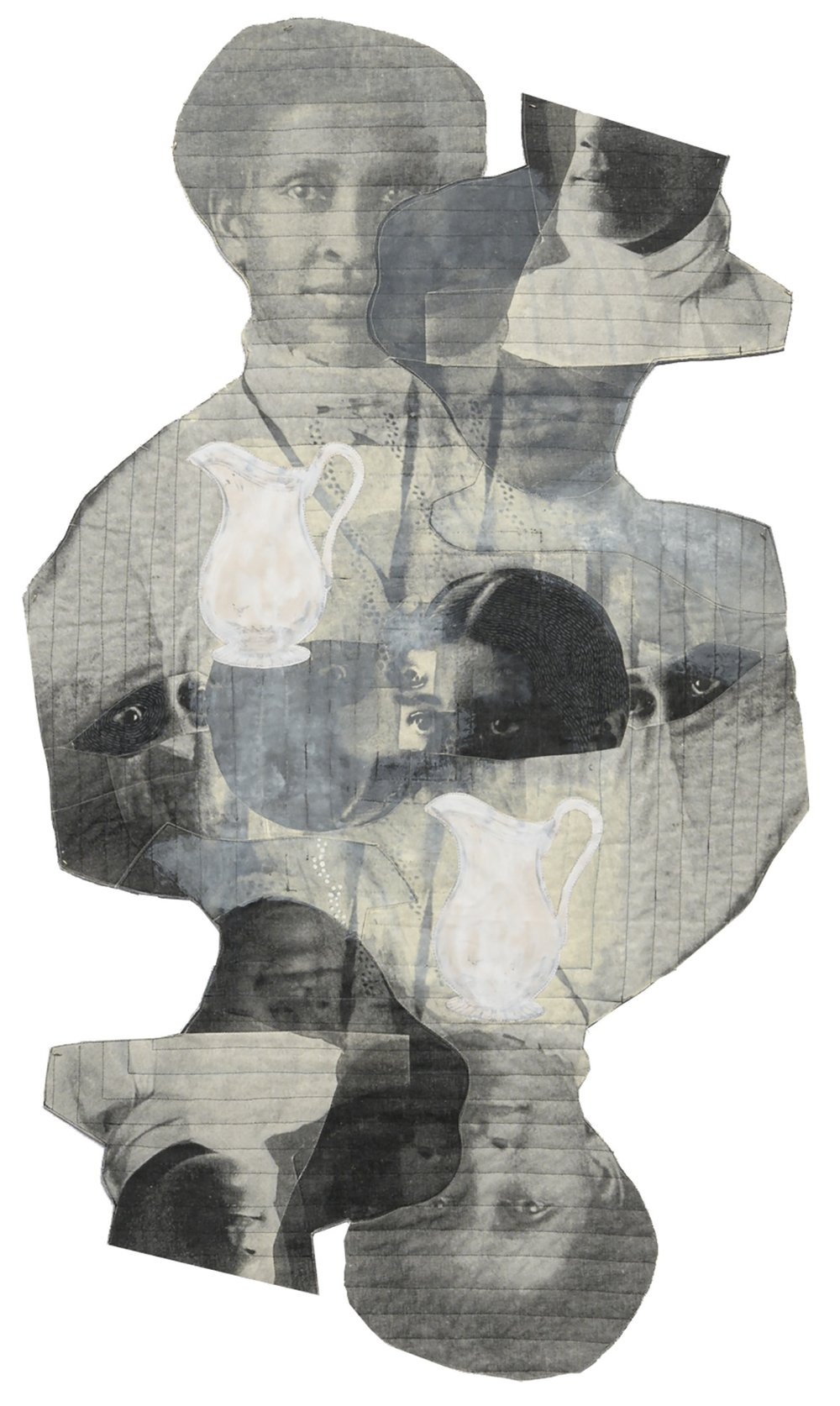

Beginning in 2022, Stephanie Santana’s ongoing project The Wayfinding Series honors Black women as “wayfinders, planners, strategists, timeline jumpers and archivists.” It incorporates photographic images, improvisational printmaking, quilting, and embroidery in prints and textile works that honor the roles and experiences of Black women, reflecting the richness and complexity of their lives and identities.

Santana’s process is more than a means of visual production; the artist uses tactile, meditative techniques that help her reconnect with ancestral wisdom. Creating an evocative and open-ended dialogue between the past, present, and future, the work invites viewers to see the connections between historical experiences and current realities, fostering a deeper understanding of the narratives she presents.

In this interview for LensCulture, Santana speaks to Liz Sales about creative processes as a way of knowing, her work’s thematic exploration and evolution, and the material and conceptual techniques she employs to assess intergenerational knowledge and encourage broader historical understandings.

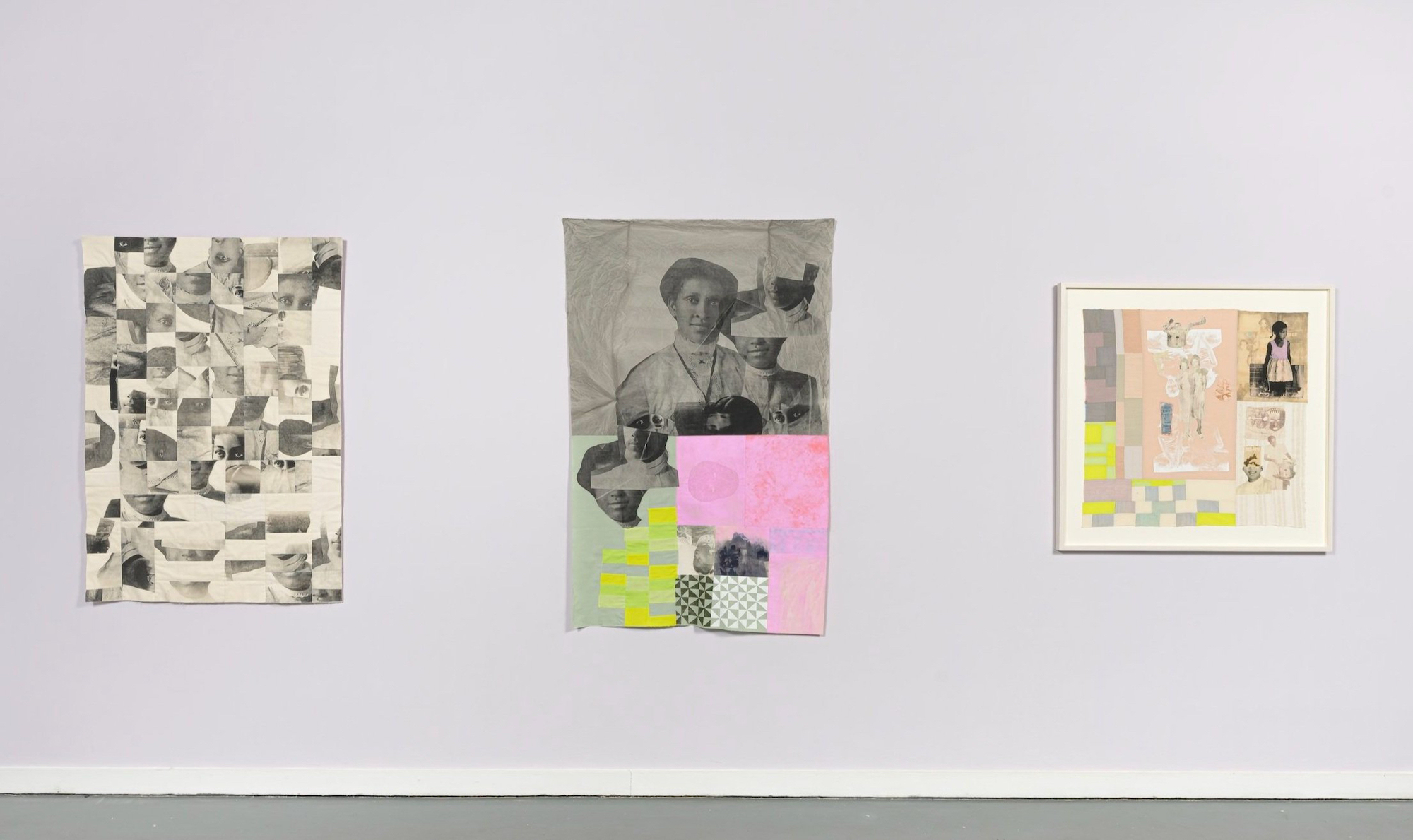

Liz Sales: Your recent solo exhibition at the Print Center in Philadelphia, PA was titled Ways of Knowing. How did you come to this title?

Stephanie Santana: I’ve been deeply interested in understanding both real and imagined matriarchal ancestors, particularly how they navigated and survived situations of oppression or being minoritized. While making this work, I realized I was creating a process that allows me to access knowledge. So, the title Ways of Knowing reflects the diverse methods I’ve explored and uncovered for understanding who we are and what we know.

LS: Would you say that your creative process itself is a way of knowing?

SS: Yes. When I stitch fabric together or engage in any physical, hands-on process, I feel a connection to my ancestors, imagining that they engaged in similar activities. Experiencing this sense of continuity with the past feels like traveling through time. Embodied making allows me to gain the type of knowledge that is passed down through generations, embedded in the practice itself.

LS: This series is part of a larger project called The Wayfinding Series. How did this project come about?

SS: Before this series, I primarily worked with family photos, focusing on commemorating specific people or events. In 2020, I created a quilted textile work titled She Sent Him Back to His Mother, featuring a photo of a relative shortly after she passed. This piece was made during a time of grieving and was meant to be commemorative.

With The Wayfinding Series, my work evolved to embed more narrative elements, worldbuilding and storytelling. Much of the work addresses the social limitations imposed on Black women and explores how we break free from those expectations. It honors us as people who know how to find a path forward when one doesn’t seem to exist.

LS: Could you tell me about your research process? How do you select the personal and historical photographs in your work?

SS: Many of the photographs in the series are from my grandfather’s work. He was a photographer and educator in Dallas, Texas, who often photographed family members and members of the community, and developed film in a darkroom at the back of his house. I’ve also worked with photographs from my great aunt’s archives. I select photographs that I’m intrigued by; whether I feel there’s something to investigate further in the subject matter of the photograph, or I’m interested in the way the subject’s gaze either meets or moves away from the camera’s lens.

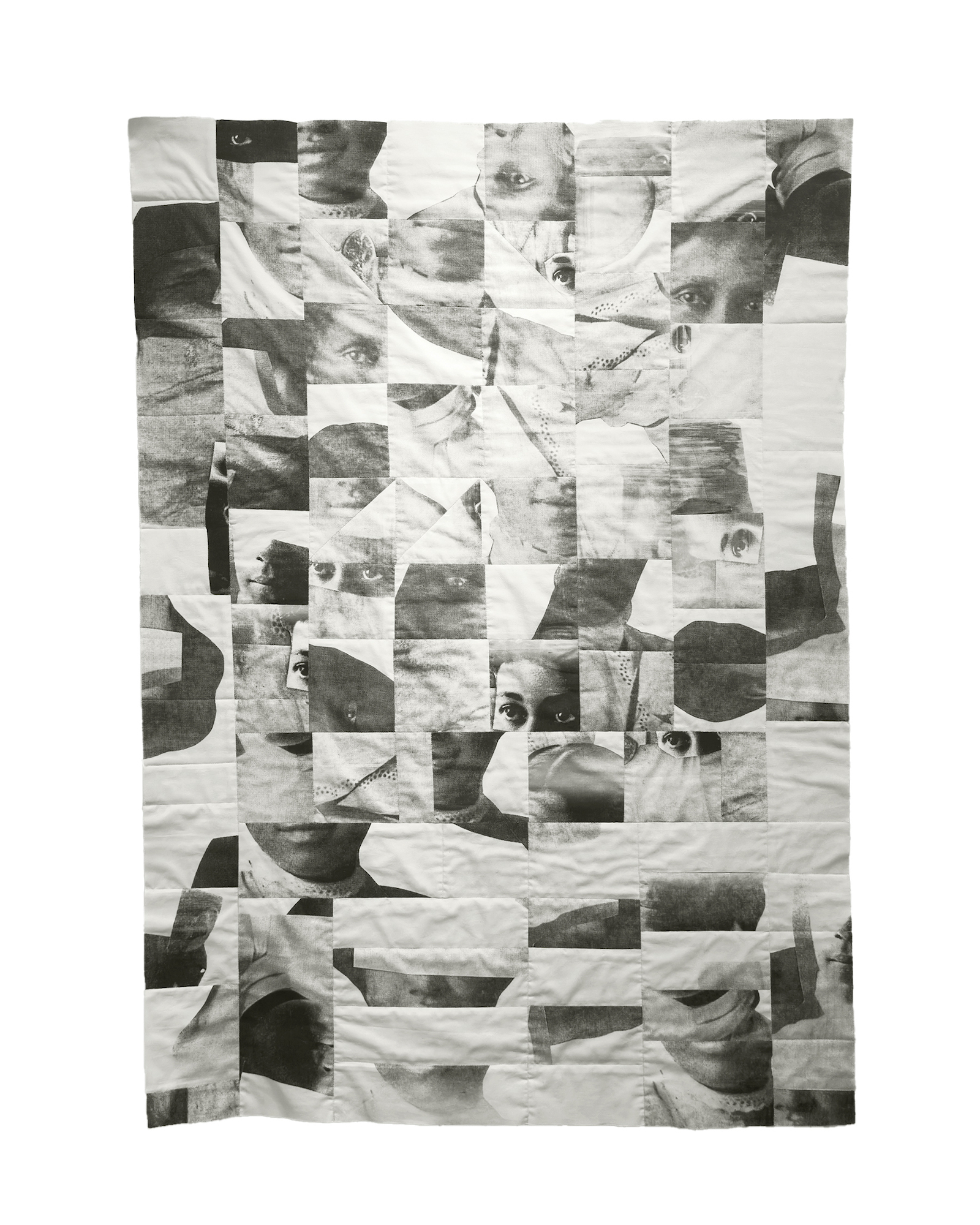

LS: I appreciate how specific images repeat throughout the work, both within and between pieces. Could you speak about that repetition?

SS: What I’m hoping to invite people to do is engage in a slower and more intimate process of looking. I see something different each time I look at the photographs I work with. I have a deep interest in exploring the truth of an image and how that can be altered or opened up to create multiple timelines and narratives. Each time I work with a photograph, the narrative shifts. This is often based on how the photograph is used in relation to other visual elements in the work, the annotations made with embroidery, color and appliqué, and so on.

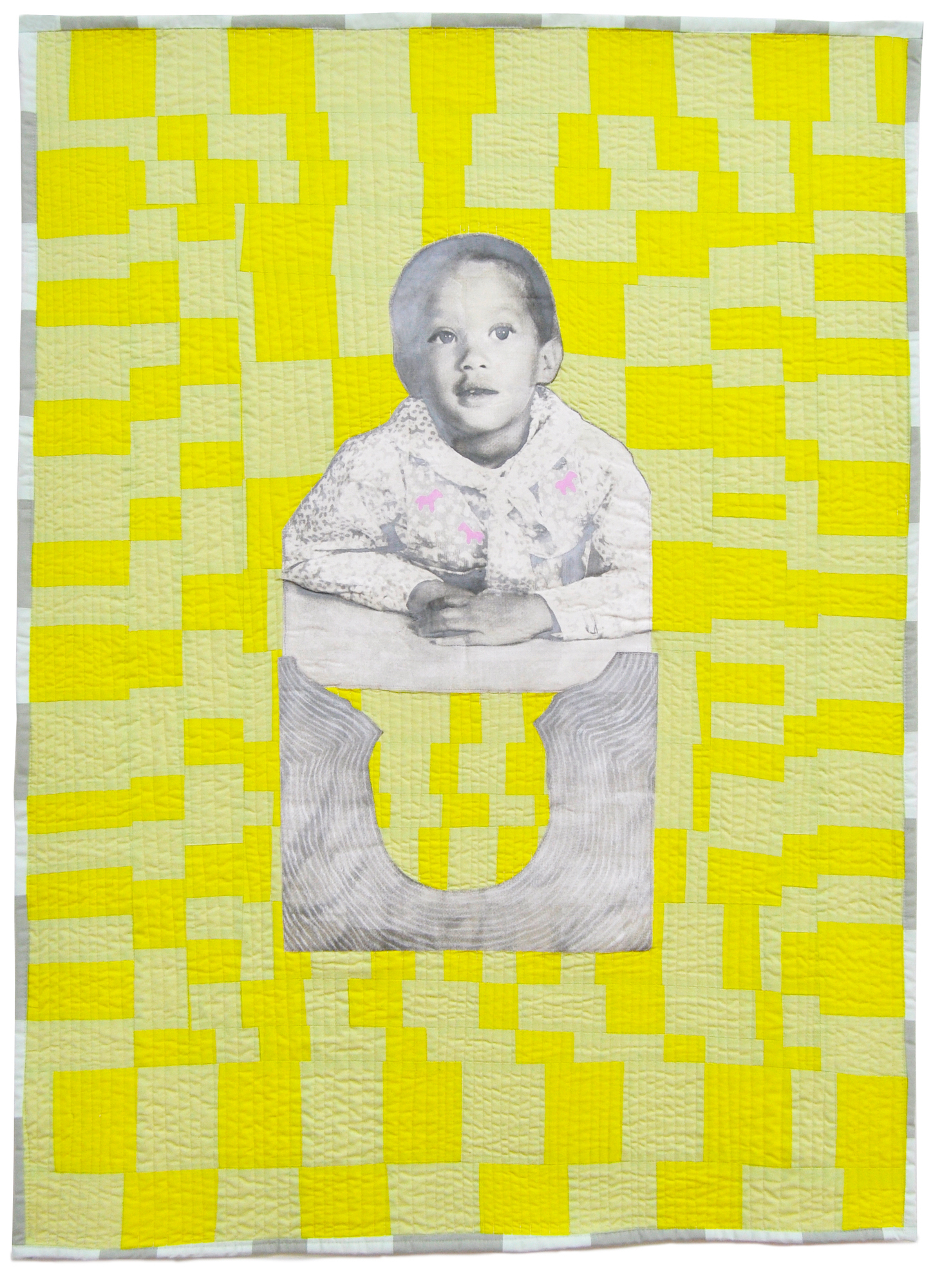

In one piece, Vantage Point, I make references to domestic labor, a recurring theme in my work. As a mother and artist constantly working with my hands, I often feel as though I’m in a continuous state of physical labor. This piece shows a little girl looking beyond the frame, away from images of women that represent the societal expectations placed on her to perform labor or present in a way that’s deemed “respectable.” In another piece I’m working on, the same image of the little girl is presented, but more of the background is visible, giving the viewer more information about a particular place and time in history. It’s a way of working in multiples as a printmaker, but exploring the possibilities of the medium in a way that’s more concerned with seeing an image or an idea with new eyes each time, as opposed to creating a reproduction.

LS: Could you detail your approach to using color?

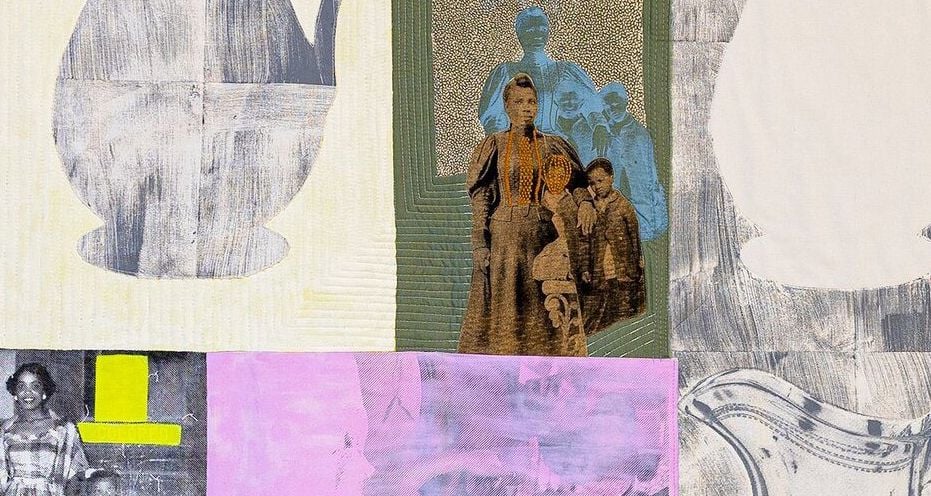

SS: In an area of the textile work Safe Passage, there’s a maternal figure standing in a protective stance with two children. The image of her and the children is repeated and changes to a sort of ‘haint blue’ as they move through a portal or passageway. I chose this blue color as an homage to the way it’s historically been used in the American south by people of African descent to ward off evil spirits, by mimicking the color of sky or water. My use of color often points to historical and/or symbolic meanings, or serves as an annotation.

LS: Are there other touch-points to help us understand your practice?

SS: Much of my work is influenced by our cultural and literary luminaries, such as bell hooks, Toni Morrison, Christina Sharpe and Tina Campt. The concept of the ‘oppositional gaze’ is central to my work: this idea and term coined by bell hooks to describe looking as an act of rebellion and site of resistance; a way for Black people to reject structures of domination and maintain our agency. Some images in my work show subjects looking off to the side, conveying a lack of concern for the viewer’s perception, while others feature a direct gaze, inviting interaction. My hope is always to encourage an engagement with the work, so that people can find a piece of it that resonates with their experiences or challenges their perceptions.

LS: Could you discuss your process regarding your materials and techniques, including printmaking, sewing, and embroidery?

SS: I often screenprint a number of images by hand and wait to use them until something speaks to me. I tend to work with a set of images at a time, and pieces will come together in conversation with each other. Hand-painting, embroidery and appliqué are ways of adding layers of time and memory. All of the quilted pieces I make are unique works constructed with hand and machine techniques, and I typically start with solid-color quilter’s cotton to allow room for adding pattern and texture that feels specific to a particular piece.

LS: What impact do you hope to have on your audience’s understanding of the themes you explore in your work?

SS: I want to invite a slower process, encouraging viewers to take their time rather than quickly moving on. I’ll refer back to Safe Passage, which references escape or finding a secure route, and points to historical moments like passage through the Underground Railroad, or the current situation in Palestine where folks have been relentlessly attacked while trying to escape genocide via designated roads that have been deemed ‘safe.’ I think a lot about our fugitive selves and how we move away from structures of domination and find spaces of recovery. This is an ongoing concern that extends through many generations and across many cultures. In making this work, I’m asking: what lessons can we learn from the past to prepare for the future?