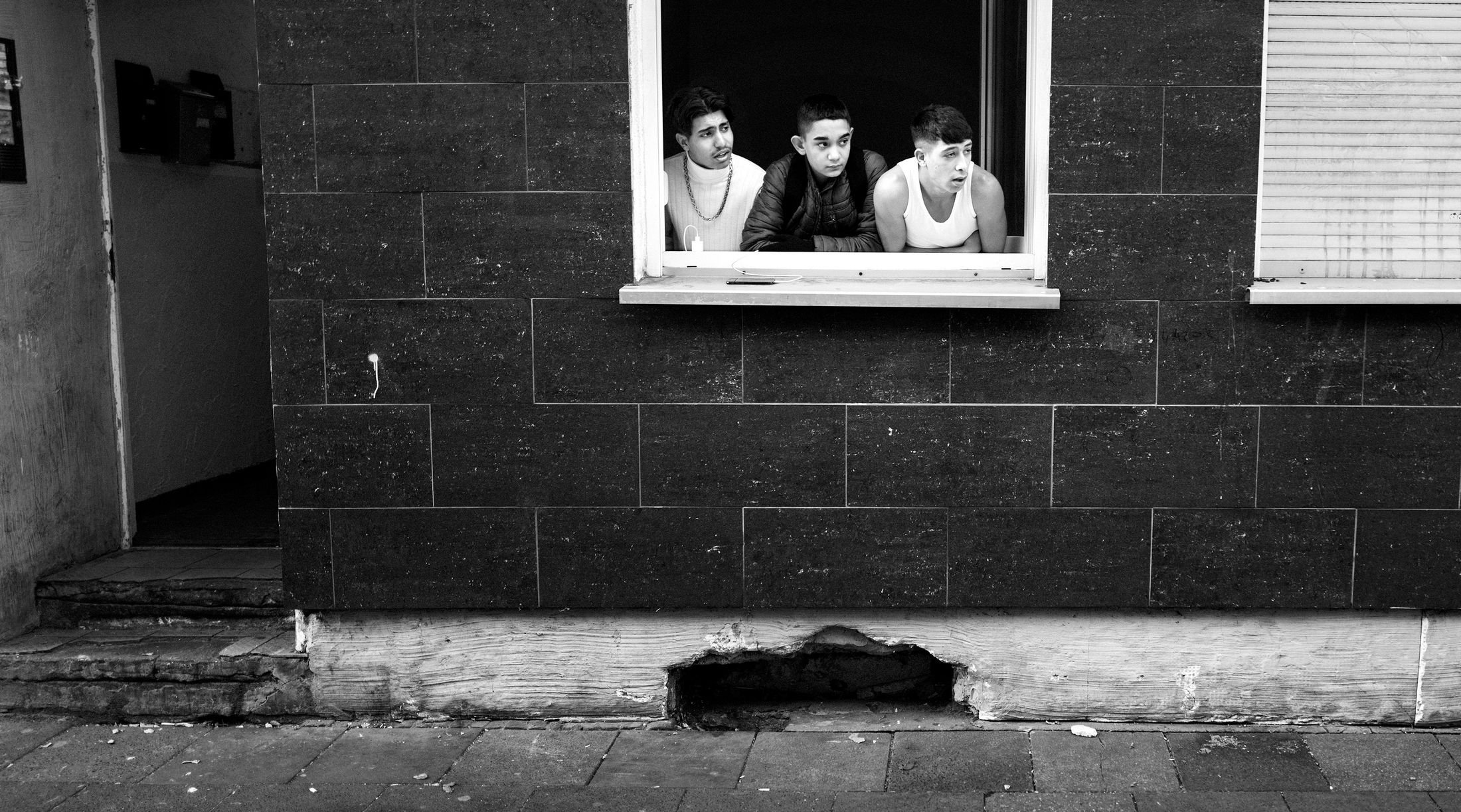

In a country where they feel like outsiders, the young residents of Duisburg-Hochfeld’s “053” neighborhood cling to a sense of belonging in a place shaped by poverty and crime. “The kids I photograph often don’t know their parents’ home country, nor do they feel accepted in Germany, so they use the digits 053 from the postcode of Duisburg-Hochfeld for identification instead. These are the 053kids… No country, no town, just the hood,” explains photographer Toby Binder. Amongst its population of 18,000, Hochfeld has the largest immigrant community of all Duisburg’s districts as well as the highest number of children.

In the rich, Industrial country of Germany, one in five children lives in poverty. Coming from families subject to discrimination, exploitation, precarious living conditions and a lack of opportunities, the #053kids are left to fend for themselves in an area dominated by drugs, prostitution and violence. Young people represent the future, and it is through this lens that Binder explores the neighborhood, providing an intimate look at the struggles these kids navigate on a daily basis.

In this interview for LensCulture, Sophie Wright speaks to Toby Binder about following young people’s stories, building a sense of trust with the people he photographs and the importance of community and solidarity.

Sophie Wright: How did you first come to photography? Did your background shape your approach to the medium or themes that concern you in any way?

Toby Binder: During my graphic design studies at the Art Academy in Stuttgart, I realized that I didn’t just want to layout stories; I wanted to experience and photograph them myself. I wanted to be out in the world, not working on a computer. Since then I have been called a ‘street dog’ more than once… and I’m happy about it.

I look for themes that I see are socially relevant. At a time when nationalism, egoism and greed are exploding all over the world—though empathy and solidarity remain strong—these topics can unfortunately be found everywhere at the moment. My own background, on the other hand, seems rather boring and sheltered. But at home, in the village where I grew up and at the football club I played for, I learned the importance of community and solidarity as a kid. Even the weak can play and contribute positively to the team if you include them. And that sometimes assisting is more fun than scoring the goal yourself.

SW: Why portraiture?

TB: Generally speaking, I see my work as documentary though portraiture is certainly an essential part of it. Showing people in their natural environment can be very powerful—especially if you don’t stage it but just take what you find. You can hardly achieve authenticity otherwise. But it only works if you actually have a documentary approach and spend a lot of time with the people you photograph.

SW: Your long-term work is often deeply embedded in the communities you are photographing and you’ve worked in various very different countries including Northern Ireland and Iraq. What would you say is the red thread between your projects?

TB: Well, I would say humanity! I often photograph communities that are marginalized or people that have not had an easy life. The teenagers I photographed in Duisburg or Belfast are growing up in a violent environment where they struggle daily for legal and illegal resources. It’s not easy to stay on the right path, but the vast majority of them are good kids!

In Kurdistan, I photographed Yazidis who are still living in tents in refugee camps 10 years after the genocide, but for whom there are hardly any prospects of returning to their homeland. Various armed groups are fighting for supremacy in this geopolitically important region. So perhaps the red thread is that I am interested in the fate of people who are trying to make the best of their lives under difficult conditions. Often I try to show the perspectives of young people. They are the future of every society and yet they often find it difficult to participate in decisions. And they are still at a point in life from which things can go in all directions. Sometimes they fail, sometimes they succeed.

SW: How did the project #053kids begin and how long did you shoot for? What drew you to this community of kids in particular?

TB: I started the series during lockdown. On the one hand, because I could not travel outside the country myself, and on the other because young people from socially disadvantaged areas suffered particularly from the measures in place. Homeschooling doesn’t work if you don’t have a computer or your parents don’t speak the language spoken in school! The kids were completely on their own for several months. No teachers or social workers were sent to these neighborhoods—only police to enforce no-contact orders. After the pandemic I just kept on shooting because I was very deeply immersed into this environment and community already. And realized that this is actually a bigger story about identity, belonging and migration in general. I’m still working on #053kids. The tricky thing is, the more long-term projects you start, the more difficult it becomes to continue them all at the same time.

SW: What struck you most about the socio-economic context these kids are living in?

TB: I found it very interesting that, at first glance, this is a neighbourhood like many others. When you look closer, you can see the aforementioned struggle for survival, through both legal and illegal means. Many parents work several shifts day and night to keep their families afloat. Most live in precarious conditions and are ripped off by landlords. The red light district and the biker gangs are visible in the streets, the illegal businesses run under the surface in small kiosks or back rooms. Sometimes it is more hidden, sometimes less.

The young people grow up with it; this is their normal. Many have long criminal records or even prison sentences as minors. In the group, they flaunt it, but in one-on-one conversations they show their vulnerability and fear. Some try to make their way by doing well at school, and often only manage this with great discipline and effort as families often live in cramped living conditions and on small incomes. A feeling of gratitude for the opportunities given is mixed with incomprehension about complicated structures that make success more difficult for young people from these areas.

SW: Tell me about the title #053kids—what does the ‘053’ stand for?

TB: It is part of the postcode of the neighborhood these kids live in. It is the only geographical location which these kids really identify with. No country, no town, just the hood! Here are their friends, here they feel at home and accepted. It is this lowest common denominator, this place of retreat that every human needs. At the same time, everyone wants to get away from here and make it to a better place.

SW: Most of the kids seem to have a complex relationship to identity. Can you elaborate on the experiences you encountered during the course of the project?

TB: When you hear the life stories of these young people, you can perhaps imagine why they don’t feel at home or like they belong anywhere. Their parents suffer from economic hardship, trying to do the best for the family, moving around a lot, always after work. The children can’t really put down roots anywhere. As newcomers, they always encounter rejection. If their attempt to make an effort to integrate goes unseen, it is difficult to remain positive—to stay away from crime and not say “fuck you all!” I am astonished and outraged that Germany still doesn’t see itself as a country of immigration. The young people I have worked with are facing the same problems as my friends from immigrant families from when I was a child. Nothing has changed. The kids have German passports, speak the local dialect but call themselves ‘Kanacken’—a German slur used against migrants or foreign citizens—as they are often made to feel that they don’t belong to this country.

One of the boys told me: “I was born in Berlin, but I am Albanian because I have Albanian blood. But I love Germany, when I’m away from here for four weeks I get homesick!” These are the realities of the lives led by our fellow citizens that politicians often fail to recognize, and who simply want simple black and white solutions. Another lived with his family in four different European countries because the father was looking for work. The boy was moved back and forth at a young age, and now speaks Italian, Dutch and German but is barely able to graduate because he is growing up in a criminalized and stigmatized environment.

There must be more equal educational opportunities in this country! But current social and political developments are of course heading in exactly the opposite direction. These children are being sacrificed by these parties and their deceitful, malicious campaigns who want to drive a wedge into our societies.

SW: How did you meet the people you photographed?

TB: When I work on projects like this, I try to communicate openly from the start why I’m here and what I want to do. This includes contact points such as youth clubs or community centers. The first contact often occurs in the streets, parks, or at the corner shop. Once you have access to a group, the rest usually falls into place. One person knows the other and gradually everyone in the neighborhood knows who I am! In cities with a lot of mistrust and many eyes on the street, it is important—also for your own protection—that you have the support of the community. Now when I come back to Hochfeld or Clonard, many of the residents know me.

SW: The portraits and the text that accompanies them are very intimate; it seems like you almost became an insider to their group. Can you tell me about how you built trust with your subjects?

TB: I am honest and open. And the kids recognize that and acknowledge it I guess. I treat them with respect and have almost never been treated disrespectfully myself. And of course I always come back, bring them the photos and the book. I do really care about what’s happening in these places and in their lives. In Belfast I used the proceeds from the book to support suicide prevention for teenagers, as some of the kids I got to know are no longer alive. Real friendships have developed and many write to me on Facebook regularly. They are interested in my life and I share that with them in the same way they share theirs with me. This applies to almost all of my projects. It’s so crazy because I came into their world as a complete stranger! They gave me access for which I am very grateful. That’s why the photos actually belong to them. I just captured them.

SW: How did you choose the locations of the photographs?

TB: I didn’t really choose them, I just follow the young people through their everyday lives. Of course, I decide when and where to press the shutter. But because I spend a lot of time with them and work very slowly, often with a slow medium-format film camera, I can usually think about locations and composition of images with enough time. If I think that a motif might work because of a visually interesting location, I wait. Sometimes it works, most of the time it doesn’t.

SW: You mention that conflicts are often resolved with violence among the groups you were working with. How did you navigate this as a photographer?

TB: Well, when it comes to young people, these conflicts are usually skirmishes, fist fights, sometimes with sticks, rarely with knives. I usually just try to stay a bit away from it. I’ve seen things that I didn’t photograph and I’ve photographed things that won’t be published. There’s a fine line when you’re very close to a group and the trust is so deep. Young people in particular are sometimes unable to see the impact of their actions on their later lives. You always want to show reality, but when it concerns minors, I sometimes have to protect them from it. When it comes to criminal offenses, I can’t use a photo where you can recognize faces. It’s different when it’s about adults who are fully responsible for what they do.

I was only able to take many pictures because of the trust of the kids. And I won’t abuse this trust. I try not to get in the way of the criminal groups that are active in these areas—with whom you inevitably come into contact as a photographer walking around there. When I see a rapid-fire weapon, I duck my head and camera.

SW: You work predominantly in black and white. Can you speak a little about this choice?

TB: Most of my long-term projects, starting with Youth of the UK to Wee Muckers – Youth of Belfast to the #053kids, I photograph in black and white. I find this appropriate for the subjects and also want to maintain the precision of the series in this way. It also gives the series a certain timelessness which means I can work on a project for years without it falling apart visually. Plus, I actually still love locking myself in the darkroom for days and making prints!

Toby Binder was awarded Juror’s Pick distinction in the 2023 LensCulture Portrait Awards.