In the hyper-masculine world of Charrería, the national sport of Mexico, Escaramuza—an equestrian performance led solely by women that bridges contemporary Mexican-American identity and the women freedom fighters of the Mexican Revolution—represents a pocket of resistance, strength, elegance and community. In this striking collection of portraits and poetry made across the United States, Constance Jaeggi explores the many layers of Escaramuza cementing its place in the often-monolithic history of the American West.

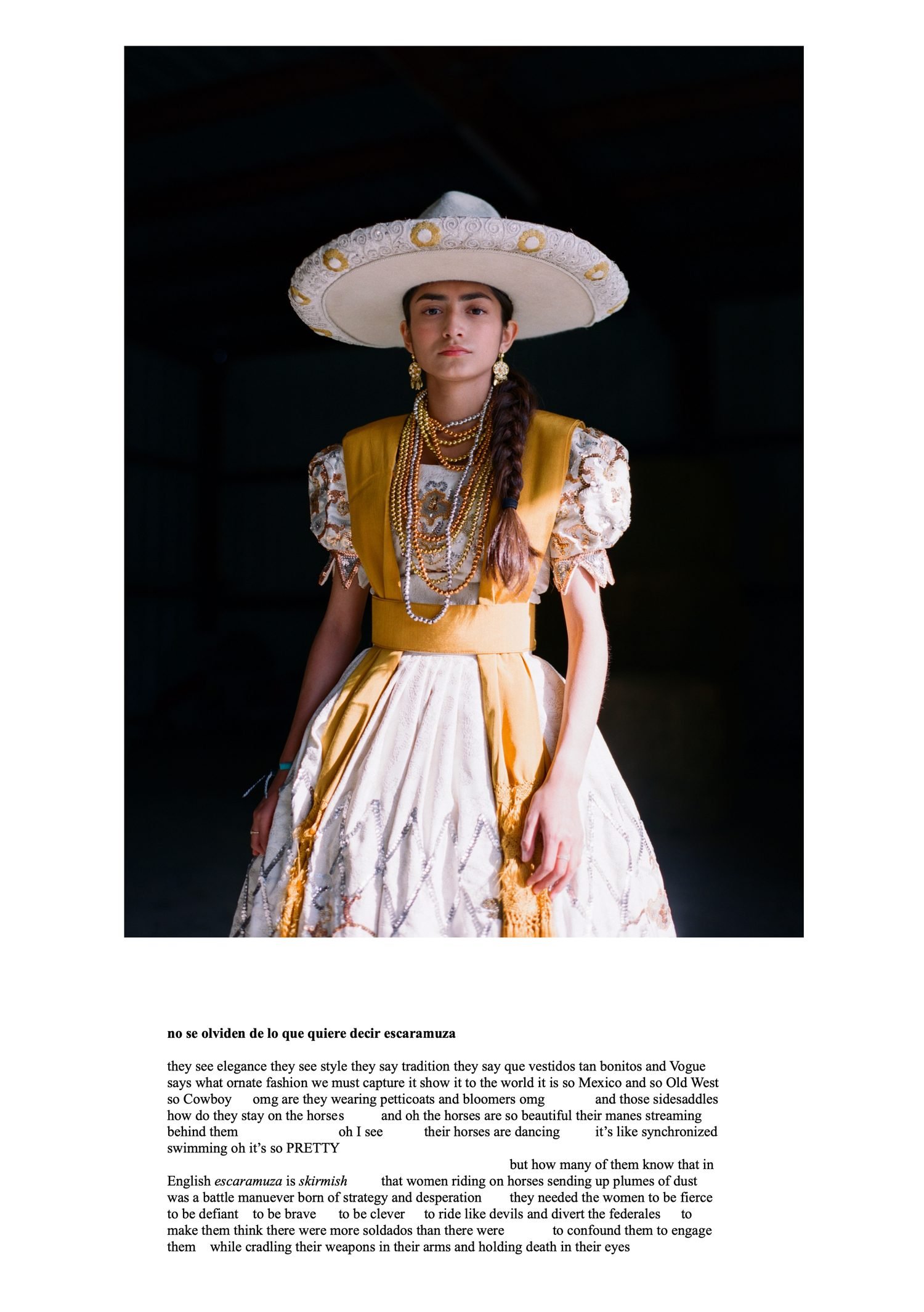

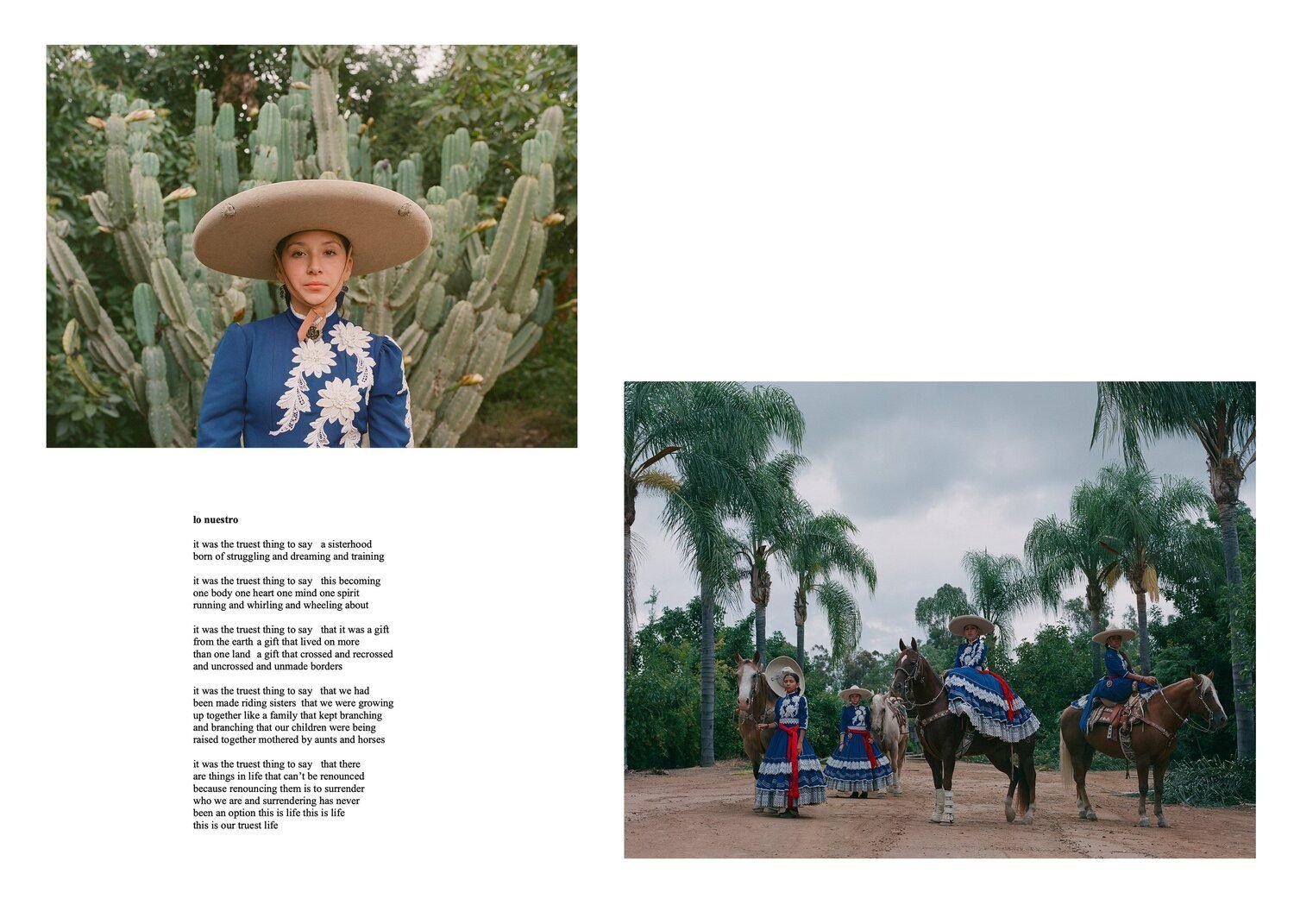

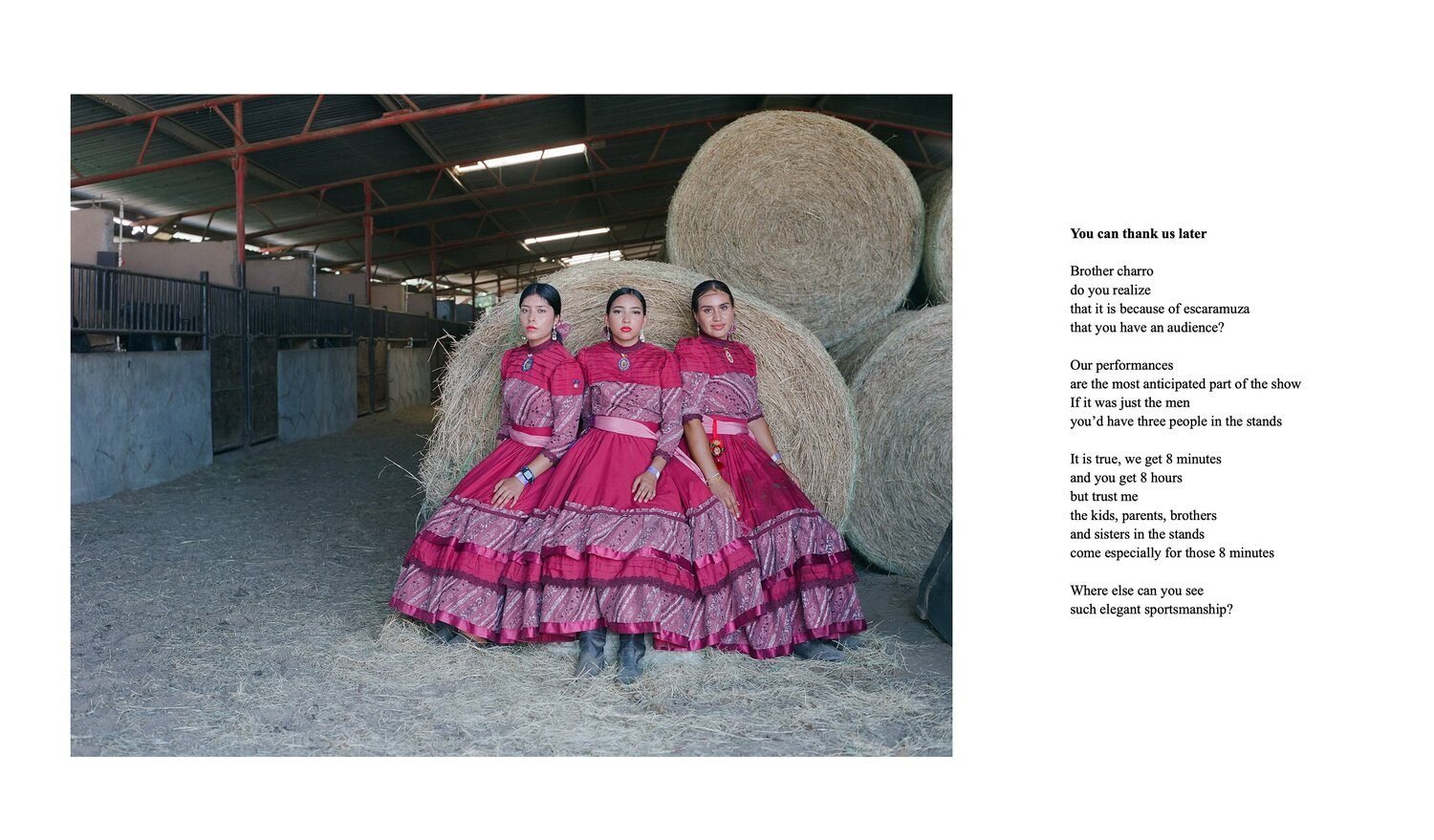

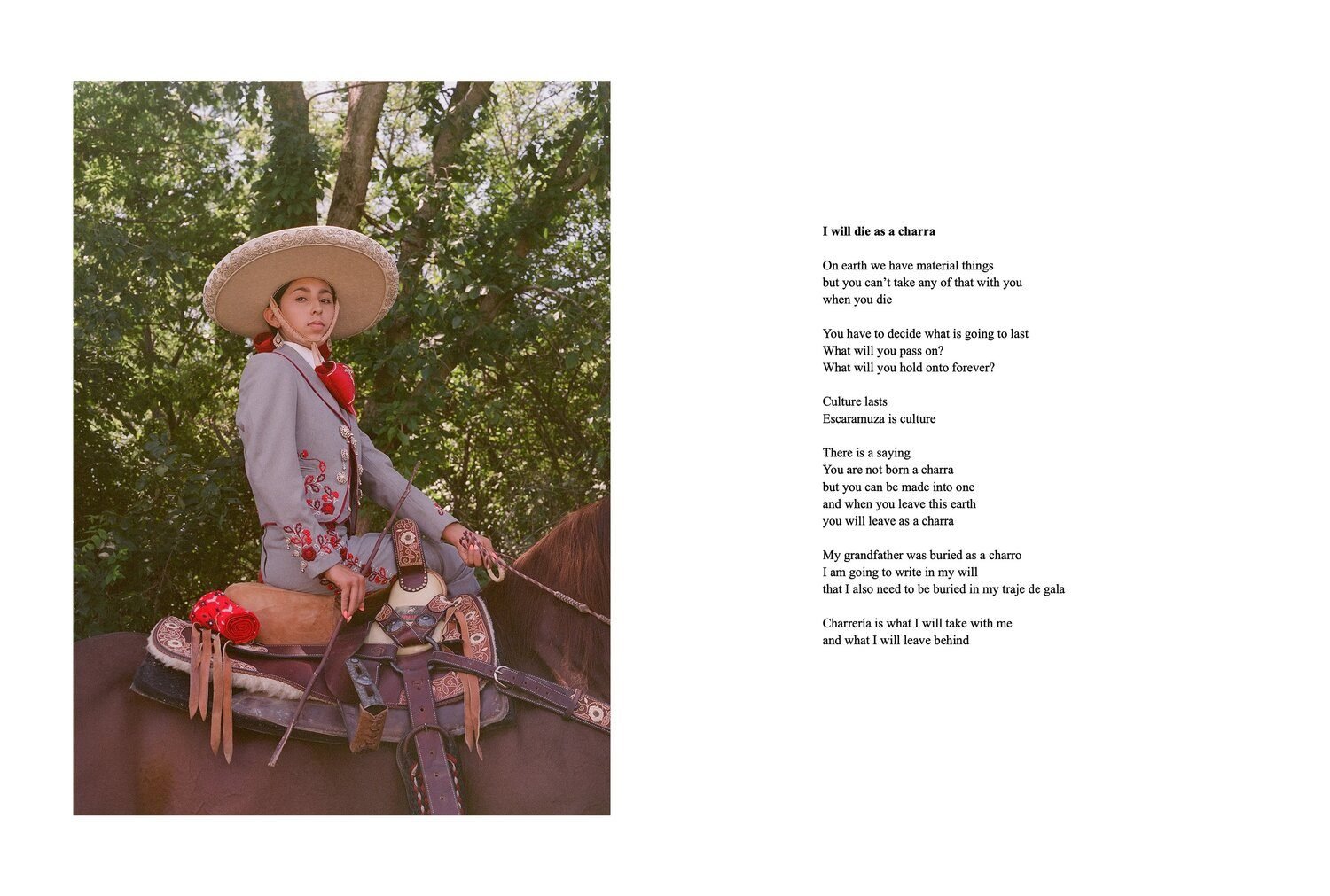

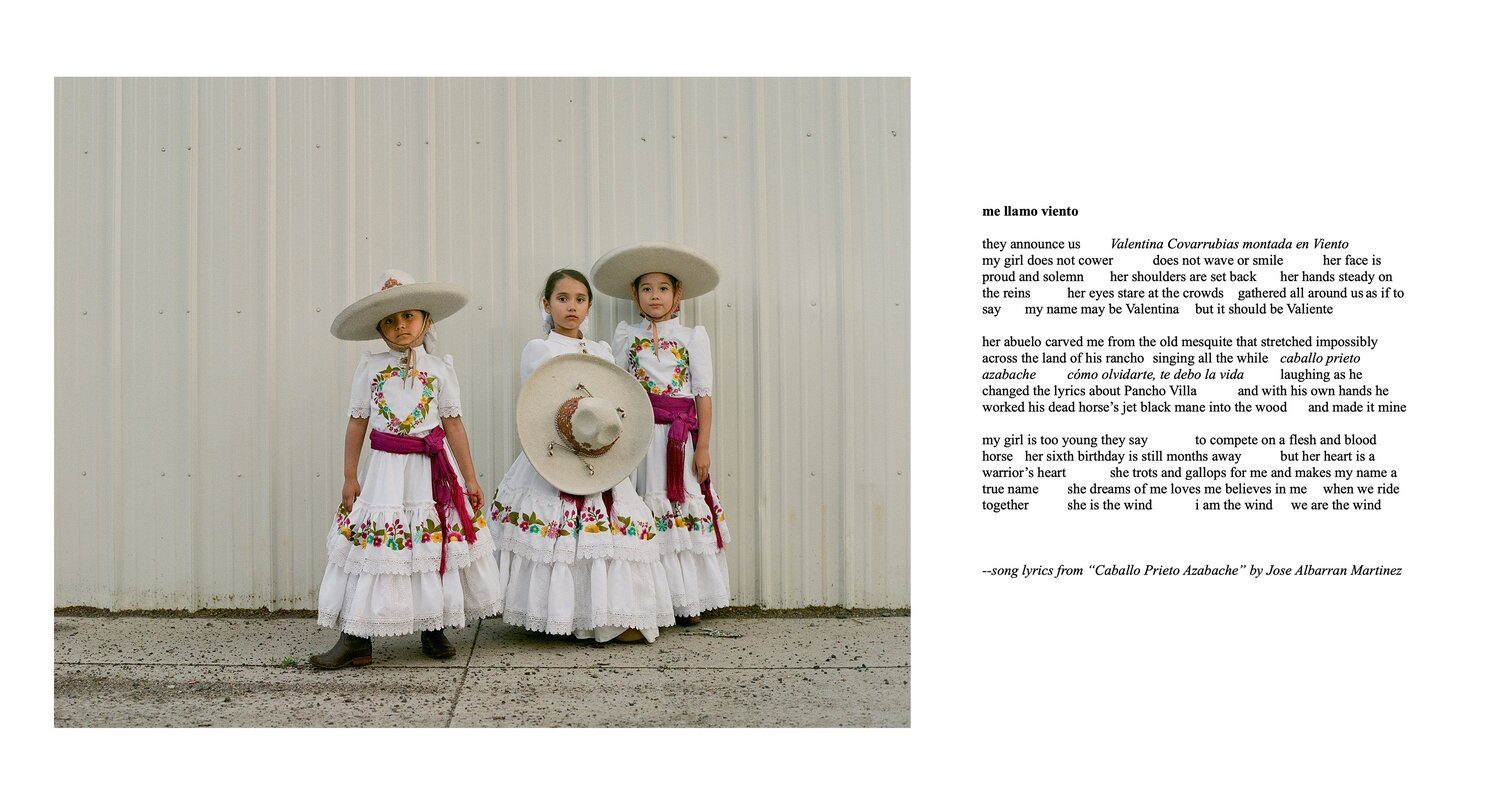

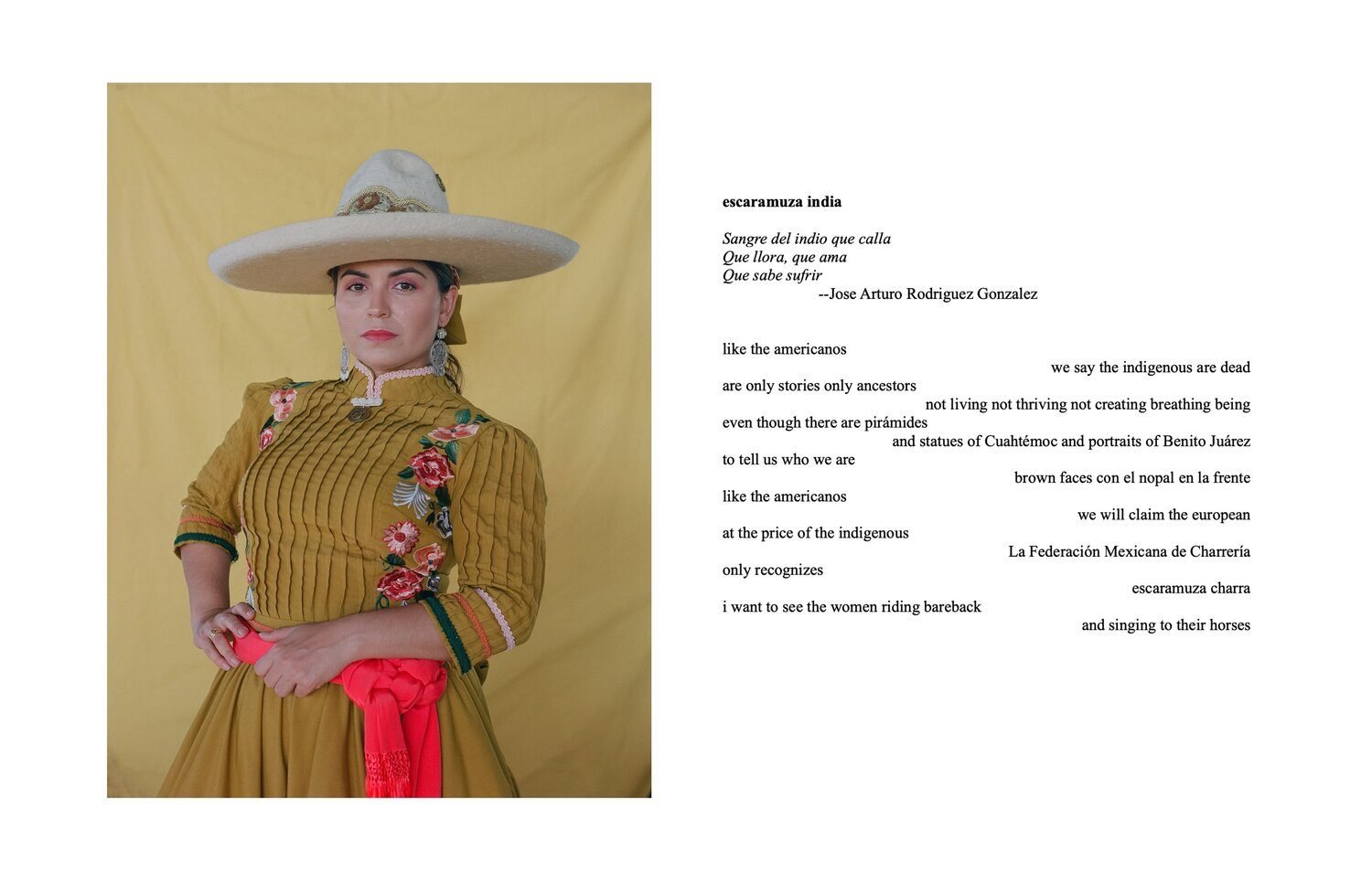

While the pictures sing with Escaramuza’s vibrant feminine aesthetics, Jaeggi chooses a more intimate and nuanced approach outside the ring of the performance itself. Photographed out in the wild landscape, sometimes in groups, sometimes alone fiercely gazing into the camera lens, the women she met are placed center stage, the portraits enriched by the words of Mexican-American poets Ire’ne Lara Silva and Angelina Saenz.

In this interview for LensCulture, Jaeggi speaks to Sophie Wright about how her own relationship to horses has shaped her life and work, the many-layered history of Escaramuza and its importance in the wider history of the United States.

Sophie Wright: Your artistic work seems inseparable with your love for horses. When did you first fall for them?

Constance Jaeggi: I was drawn to horses from a very young age growing up in Switzerland, just outside of the city yet far from rural and farm life. That draw was strong enough to steer me into a somewhat unexpected direction. In my early teens, I started riding at a western riding barn near home and developed a passion for all things ‘western,’ in part shaped by the romanticized portrayals of the American West I had seen in films and heard of in music. When it was time for college applications, Texas was the obvious choice. In Texas I could pursue a competitive cutting horse-riding career while earning a bachelor’s degree. I could be a cowgirl.

SW: And how did photography come into the picture?

CJ: My new life in Texas as a competitor and rancher revolved entirely around horses. Throughout college, I was spending all my weekends and free time on horseback. I spent a lot of time on the road on the competition circuit and after graduation was fully dedicated to my competitive career.

Eventually, I felt compelled to explore the horse and my relationship to them visually. Having grown up with an appreciation for visual arts, it was almost impulsive. I didn’t think much about it at the time. I just picked up a camera and started photographing. I found that it fulfilled a part of me that I hadn’t tended to up until then as well as deepening my connection and understanding of horses. I was curious about the age-old human-horse relationship and how that impacts our relationship with horses today. Photography was a way to lean into that curiosity and express myself differently.

SW: Your projects explore the themes of intimacy, identity, connection, power struggle and womanhood. Can you talk a bit about how our relationship to horses provides you with the lens through which to examine these ideas?

CJ: My relationship with horses has been fundamental to my growth as a person. As a child, I was extremely shy, but horses helped me assert myself. Riding a thousand-pound animal with a mind of its own taught me to be both decisive and attuned to an animal that can’t explicitly communicate its feelings—sort of like learning a foreign language. While on the competition circuit, I traveled the USA in a way most Europeans don’t, seeing parts of small town and rural America which has shaped my perspective and continues to inform my work.

I am also interested in the history of the human-horse relationship. Horses were integral in the development of civilizations as beasts of burden and instruments of war. Before the advent of motorized vehicles, they expanded human horizons, enabling us to cover vast distances that would have been impossible on foot. Yet, this partnership with horses is steeped in paradox. Despite their natural instincts as herd and prey animals, which drive them to flee from danger, they have become symbols of force and power when united with humans. This raises intriguing questions about the nature of our relationship with them and the fine line between partnership and usership.

My perspective as a woman plays a role too, in how I approach photography. I find more common ground with other women in how they relate to horses. I know that relationship, and I photograph what I know and connect with. While we rely on their strength and capabilities, horses are inherently more powerful than we are. Their role in our lives underscores a complex interplay of power, dependence, and mutual benefit. This intricate relationship is deeply woven into my identity, continually shaping how I perceive and navigate the world.

SW: You are Swiss but relocated to Texas. I once heard someone describe an affinity between Alpine cow herding culture and cowboy culture. Do the two places share a connection for you at all?

CJ: I had little connection to the Alpine cow-herding culture, or to farm life when growing up. My exposure to horses and western horse-back riding became a window into a different way of life. Texas, with its vast opportunities in the western equestrian world, its wide-open spaces and the chance to forge my own path, offered me everything I was yearning for at that time.

I have grown roots in Texas. My European heritage has undeniably shaped my values and perspective, as has my life in the United States and this blend enriches my understanding of the world. I’m not sure that I view them as connected but rather as complementary perspectives. It’s a strength to have both, even if it means not feeling that I fully belong in either place. I’ve grown comfortable being in between the two; I feel that I can see more from that vantage point.

SW: Can you tell me about the tradition at the heart for your project Escaramuza, the Poetics of Home and how it has evolved over time?

CJ: Historically Charrería, which is the national sport of Mexico, was predominantly male. Charrería emerged from early Mexican cattle ranching activities and was eventually refined and formalized during the post-revolutionary era as a romantic, nationalist expression of ‘lo mexicano’ (Mexicanness). It is similar in many ways to American rodeo in its variety of competitive equestrian activities. Women, however, were not seen participating on horseback until the 1950s when they were finally brought into the sport as riders.

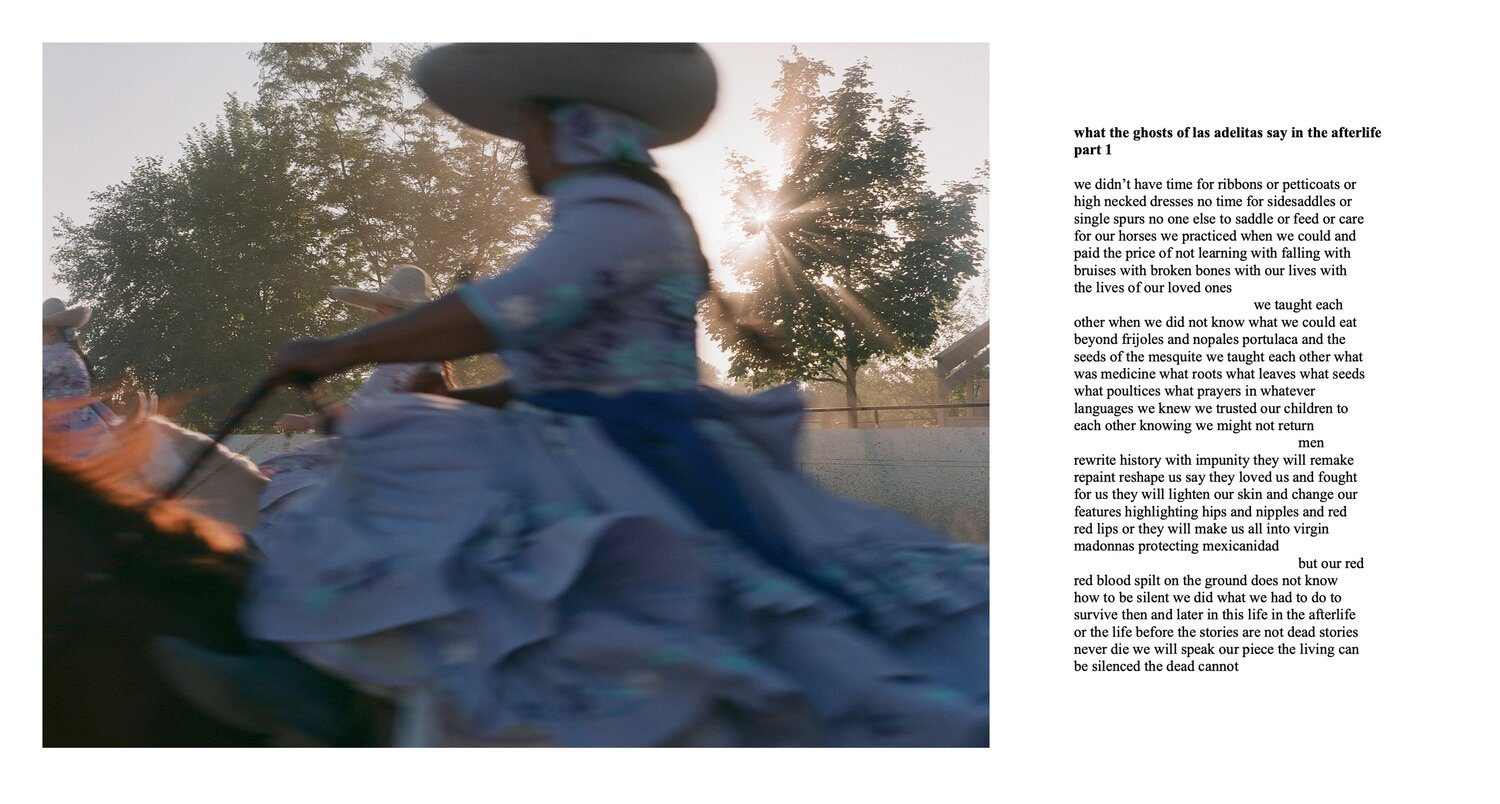

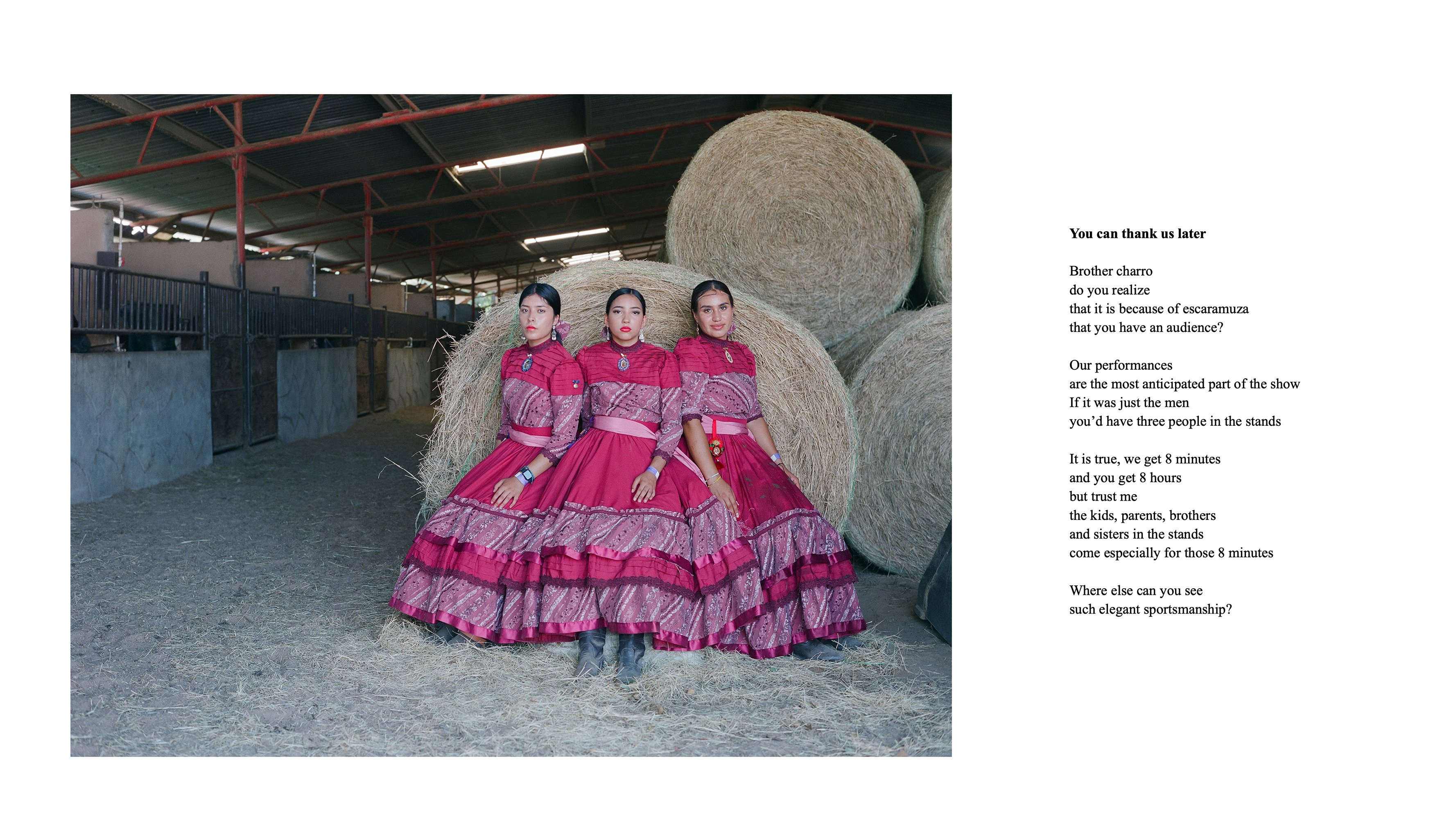

A discipline was invented for female participants called ‘Escaramuza,’ consisting of all-female precision horse riding teams who execute exacting maneuvers while riding sidesaddle at high speed and wearing traditional Mexican attire. The costumes and synchronized patterns they perform were inspired by the Soldadera or Adelita, the women who fought in the Mexican Revolution between 1910-1920. To this day, the events within Charrería remain heavily gender segregated. A charreada lasts up to three hours but the portion dedicated to Escaramuza makes up for three to five minutes of those three hours, so there is still a large discrepancy between the representation of genders within the sport.

SW: What was it about Escaramuza that caught your imagination?

CJ: Escaramuza is wide-spread in Mexico of course, and becoming increasingly established in the United States as Charrería keeps growing. Initially, I was drawn to the visuals. The dresses are colorful and intricate, and the performance is elegant and powerful, like a ballet on horseback. But it is the stories of the women I met that really captivated me. The dedication that they have for the sport and their drive to uphold this tradition is admirable. In Mexico, Charrería tends to be a sport practiced by the wealthy, while many of the charros and charras in the US work hard to be able to afford the costs associated with owning and competing with horses. A lot of the women I met are full time students, or have full time jobs, sometimes multiple jobs and are raising children.

The sport is also dangerous. The women ride side saddle in heavy, hand-crafted dresses. A team consists of eight riders, and they perform patterns, criss-crossing each other at high speed. Riding side-saddle is extremely difficult as you only have good control over one side of the horse. There is a narrative around immigration and the role it plays in the development of the sport in the US, shaped by this feeling that many of the riders expressed to me of “not feeling Mexican enough when traveling to Mexico, but not feeling American enough at home either.”

Then there are the gender relations. Many riders expressed frustration regarding their inability to vote within the Charrería governing association, and the strictness of the dress rules they are subjected to, which is not the case for the disciplines practiced by the men. And finally, the parallels with the women who fought in the Mexican Revolution, the lack of historical research on their role, how they were remembered through time. Essentially, it felt like such a richly layered story, there was so much unpacking to do that I couldn’t look away.

SW: Who are the women in your photographs and how did your collaboration with them develop over the course of the project?

CJ: The women I photographed are from all around the US. They are for the most part first, second, third, fourth and fifth generation Americans. As I got to know these women personally, I became aware of the importance of their oral histories. I needed to bring their voices back into the work somehow. I started interviewing teams as I went. I met teams from California, Texas, Washington, Illinois, Iowa and Colorado, recording their stories as I photographed them. I tried to understand how they thought of their position in Charrería, what Escaramuza meant to them and how they wanted to be seen, which influenced the way I photographed them. I am continuing the project as I expand the body of work for an upcoming book, and attempting to cover as many of the US states as possible.

SW: Can you elaborate on Escaramuza’s roots in the revolutionary movements of Mexico? How does the tradition translate into Mexican-American identity for the women practicing it?

CJ: Escaramuza translates to ‘skirmish’ in English, inspired by the image of the soldaderas sent into battle before the men to kick up dust and distract the opposing side. Women of course played a much more significant role than simple distraction during this complex and destructive civil war. They were activists in feminist movements, but a much larger number of women of rural and lower urban classes found themselves caught up in the struggle and had no choice but to be actively involved, whether it was as camp followers and caretakers for the soldiers, or as women who took up arms.

I see parallels between the soldaderas’ contribution to the advancement of women’s emancipation in Mexico and the Escaramuzas I met who are pushing back on the machismo in their sport. Especially for the US-based Escaramuzas growing up in blended cultures. The image of the soldadera is a powerful historical example and reference point. It means that Escaramuza is much more than a way to connect with contemporary Mexican traditions. It also connects these women to their history, the history of their people and of women in their culture. It gives women a certain image of strength to refer to.

One of the riders told me that she wanted to inspire other young women by showing them that they too could ride horses, be fierce and competitive and that they too could have a place in Charreria. Soldaderas provide evidence of women defying social expectations, and that has an impact.

SW: How did you navigate your position as an outsider encountering the Escaramuza community?

CJ: The community was very welcoming and willing to work on this project. I think that having a connection to horses was helpful, but I was very aware of my position as an outsider insofar as I was photographing a tradition and culture that was not my own. Photography can be objectifying, by turning people into simply beautiful objects to be admired and possessed and I wanted to make sure that was not the case for these women. Their personal experiences needed to be present in the work.

This was challenging given the aesthetic nature of Escaramuza which is easy to appreciate for its beautiful colors and formality. There is a lot of pride in the tradition that translates to their physical presentation. The women take a lot of care in doing their hair and makeup and presenting themselves respectfully because, in their words, “when we wear our Adelita dress, we represent Mexico.”

SW: Can you tell me about threading other voices into the project through your work with poets Ire’ne Lara Silva, and Angelina Sáenz, and what that collaboration brought to your process?

CJ: I had hours and hours of recorded interviews that gave strong insights into the landscape these women were moving in. Poetry felt like a great way to layer the narratives and an opportunity to add some real depth to the work. There was also something about juxtaposing the immediacy of the photographic medium with poetry which appealed to me. Poetry is a slower experience that engages you very differently.

Ire’ne Lara Silva and Angelina Saenz are both very accomplished poets. Ire’ne is the 2023 Texas state poet laureate and Angelina is an award-winning poet and educator and UCLA writing project fellow. As Mexican American women from two different states, they were well positioned to be the ones tasked with amplifying the voices of the Escaramuzas and contextualizing their experiences. I think I learned just as much from them as I did from the Escaramuzas I worked with.

Angelina and Ire’ne took slightly different approaches to writing. While Angelina focused more on the interview recordings, Ire’ne incorporated the history of the soldadera. I love that this body of work is both multicultural and a female-driven story. Ire’ne and Angelina broadened the perspective of the project and provided another window into the human experience.

SW: There is a stark aesthetic leap between your past projects, shot in black and white, and the colorful, formal approach you take in this body of work. Can you talk me through this new direction and the choices behind it?

CJ: This project took me out of my comfort zone photographically in many ways. Up until then, most of my work focused on the horse and I had little experience making portraits of people. I had also been shooting mostly black and white film and working in a studio setting. A lot of thought and care went into how I chose to photograph these women, to convey their strength, and the power of the tradition. There is a certain formality to the tradition in the way they dress and a rigidity in the rules governing women’s attire in Escaramuza that I wanted to respect. But I also wanted to convey their assertiveness, so the gaze was essential. These are women confronting the camera, owning their place in Charreria and in the American landscape.

SW: In contrast to the ‘lone ranger’ cowboy archetype of the American West, the visual narrative of Escaramuza pictures a team effort practiced solely by women. Can you elaborate on the role of community that you encountered during the making of the project?

CJ: Historically speaking, Charrería is a forerunner to the North American Rodeo and therefore crucial to incorporate into the history of the American West. The nature of this region’s history is multifaceted and complex and that needs to be reflected in the stories that we tell. While the portrayal of the “lone ranger” cowboy centers on a rugged, solitary figure battling for good against outlaws, it simplifies the complex and diverse experiences of the American West. To shift that narrative, we need to be more aware of the blending of cultural traditions in this history, but also the blending of gender roles. Escaramuza shifts the narrative by focusing on the experiences and contributions of women in Mexican charro culture and emphasizing community, family, and cultural heritage.

SW: The passing down of culture to next generations, not only through the technique but also through traditional dress and in the accompanying poetry, seems like the heartbeat of your project. What would you say is Escaramuza’s relevance in contemporary culture?

CJ: I believe it is relevant in many ways. For one, Escaramuza is an example of cultural preservation in an era where globalization often dilutes local traditions; a way of keeping customs and stories of past generations alive by passing down skills and technique from one generation to the next. It is a celebration of heritage. It is also a source of personal empowerment for many of the women involved, providing a strong sense of identity and pride and challenging traditional gender roles by showcasing women as skilled equestrians and leaders in their communities. This empowerment is not only personal but also communal, as it helps redefine gender norms within a cultural context.

I have come to think of Escaramuza as a sort of road map. It contributes to a sense of understanding, for the practitioners, of where they come from, where they are going and who they are. It’s a uniting element between generations, between family members, between past, present and future.